There was no way for Carolina Sanchez to isolate herself from her family after testing positive two weeks ago for COVID-19.

She lived squeezed into a room with her four children at a Vagabond Inn in Sylmar in the northeast San Fernando Valley. They and Sanchez’s sister, who looked after them while she worked at a 99 Cents Only store, also contracted the virus. This was the cost of being a low-wage worker living in crowded conditions. It was a cost exacted from Latinos above almost any other group.

“It is scary knowing that you could go out there and get sick again,” she said. “I’m even scared to go back to work because of people coming in and out [of the store] and it’s people that could be sick and are still going out to shop.”

With coronavirus reaching unprecedented levels in California, the pandemic is once against stalking low-income, working-class, majority Latino neighborhoods with a particular aggressiveness, according to a Times data analysis.

Newsletter

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In Los Angeles County, which is a major COVID-19 epicenter, five of the 25 communities with the highest infection rates are located in the northeast San Fernando Valley, in areas that are home to “essential” workers at prime risk of getting COVID-19, and include ZIP codes with high rates of crowded housing. Some are plagued with pollution and are encircled by three bustling freeways, a railroad line and dozens of industrial facilities, as well as a power plant that for three years had been leaking methane.

Near the top of this troubling list is the city of San Fernando, which has an infection rate that is two times greater than that of L.A. County as a whole. Its rate as of this weekend was 1,044 cases per 100,000 people, compared with the county’s rate of 496 per 100,000, according to government records. Also badly hit is the L.A. neighborhood of Pacoima, which has an infection rate of 993 per 100,000 people.

The Valley neighborhoods of Arleta, Sylmar and Van Nuys are also on that list.

While 11% of homes in L.A. County are considered crowded, some of the neighborhoods with the highest rates of infection — including Pacoima and Arleta — have rates of crowding twice as high, according to a Times analysis.

The trend reaches beyond just Los Angeles.

A Times analysis of communities statewide showed that other heavily Latino areas are among the hardest hit. Such communities along the 10 Freeway corridor in San Bernardino County have among the state’s highest case rates, including in Bloomington, Colton, Fontana, Montclair, Rialto and San Bernardino, as well as those in the high desert, such as Adelanto, Hesperia and Victorville.

They stretched statewide, in border communities in San Diego and Imperial counties such as Calexico and San Ysidro; agricultural communities in the Central Valley and Coachella Valley; and a community in Berkeley, where an outbreak has spread among hundreds of workers at the Golden Gate Fields racetrack.

Latino workers have the highest rate of employment in essential frontline jobs where there’s a higher risk of exposure to the coronavirus, according to the UC Berkeley Labor Center; 55% of Latinos work in such jobs and 48% of Black residents do as well, compared to 35% for white residents.

Michael Villalobos, left, a community intervention worker with Soledad Enrichment Action in Los Angeles, carries a bag of donated groceries for Kameo Allen, right, of Lake View Terrace and her daughter Bella, 3, on Nov. 12.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

As of Nov. 7, Latino residents were being hospitalized at an age-adjusted weekly rate of about 10.5 per 100,000 Latino residents, or more than double the rate of 3.8 hospitalizations per 100,000 white residents. (Statistics adjusted to account for age differences among racial and ethnic groups provide more meaningful comparisons, according to epidemiologists.) The disparity in death rates had been declining, but could worsen as the death toll rises.

‘While, once again, we were making progress in reducing the gap amongst people of color when compared to white and Asian residents, we will face a similar fear of a widening gap should we see our death rates continue to go up,” said Barbara Ferrer, the L.A. County director of public health, in mid-November.

In July, the nonprofit Meet Each Need With Dignity, or MEND, which runs an emergency food bank in Pacoima, began conducting a housing survey of new clients and collected data on 414 households located in the northeast San Fernando Valley. The survey indicated that 41% of those residents share a household with another family and more than 30% live in a back house, room or mobile home. About 8% lived in a garage.

“Most live in some sort of substandard living, so they could be living in a garage with no heat or air conditioning,” said Janet Marinaccio, president and chief executive of MEND. “There can be a family of six living in a garage. They’ll double up and triple up, you might have four families, one in each bedroom and living room.”

This week, the L.A. County Department of Public Health expanded testing in this corner of the Valley. It also increased outreach efforts in the Latino community with the help of promotoras, trained lay health workers who can provide information about the pandemic to the public, including in Spanish.

Early last month, the county dedicated about $30 million to the program as cases of COVID-19 soared.

The alarming number of people becoming infected in the San Fernando Valley is due to a variety of reasons, including colder weather forcing more people to cluster indoors. Ferrer believes a false sense of security has also settled in among a lot of people.

“I think it may more reflect the gatherings and the parties, the mixing with people not in your household,” she said. “And one problem with this virus is once the rates go up, it can kind of feed upon itself.”

Gladys Ayala, chairwoman of Chicas Mom Inc., a nonprofit that aims to educate and empower women in the northeast San Fernando Valley, said shame and inconsistent information from the White House increased doubt about the seriousness of the coronavirus.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

Gladys Ayala, co-founder and chairwoman of Chicas Mom Inc., a nonprofit that aims to empower and educate women in the Valley, said shame and inconsistent information from the White House increased doubt about the seriousness of the coronavirus. She said she tested positive for the coronavirus in May and infected her family.

“The president had a lot to do with this,” she said. “He minimized this so much that people didn’t believe it.”

Ayala said she had all the classic symptoms, losing her sense of smell and taste, and felt fatigued. Her husband, who is diabetic and has high blood pressure, was hospitalized for three weeks. They both recovered. Her two children, ages 19 and 15, tested positive but didn’t develop any symptoms.

Sanchez, 28, the mom living with her kids in a motel, said she had returned from working a shift at the 99 Cents Only when she felt sick. She developed chills, lost her appetite and had trouble breathing. After three days in bed with a fever, she went to get tested while her children slept and found out she had COVID-19.

“I had always tried to stay safe with my mask on, I wear my gloves and keep my distance as people come in,” she said.

For two weeks, she quarantined with her four children — ages, 3, 4, 5 and 8 — and her sister in their room. She said none of the children developed symptoms.

The situation was another marker in Sanchez’s hard life. She’s a domestic violence survivor and for five months she lived in her car with her children after being evicted from their home.

A year and half ago, she enrolled in an L.A. housing program that pays for a large portion of her rent at the hotel. Sanchez said she pays about $275 a month and had gotten her job in July.

Sanchez said family members come by to drop off meals outside her motel room. She said the children have grown antsy because they want to go outdoors. She said her 8-year-old, Nathan, who is attending classes online, has had a hard time concentrating on school.

“The space is limited, so he has his brothers jumping up and down in the background,” she said. “I have teachers call me and tell me Nathan needs to be in a quiet place to do his homework.”

When the latest surge in COVID-19 cases erupted, 34-year-old Pacoima resident and community activist Silvia Anguiano picked up the phone to reach out to nonprofits like Homies Unidos, 2nd Call and Partido Nacional de La Raza Unidas.

Anguiano was particularly worried about how the pandemic could tear through the community of immigrants who are living in the country illegally.

“They don’t have health insurance, so they don’t know where to get tested,” she said.

“One out of two immigrant people in the community don’t know where to get tested, so we need to bring some kind of education and program to our food distribution,” said Alex Sanchez, 49, an organizer and co-founder of Homies Unidos, a gang-intervention nonprofit that also aims to empower youth.

Two weeks ago, the group had its first food giveaway event outside of Hubert H. Humphrey Memorial Park in Pacoima. Black and Latino men and women wore masks and gloves as they unloaded boxes filled with milk, hummus, watermelons and vegetables while cumbia music blasted from a speaker in the background.

The event caught the attention of people driving by and residents living around the park who arrived with shopping carts and baby carriages. They were all given bread and hand sanitizers while volunteers filled large bags with groceries and placed them in the car trunks and shopping carts.

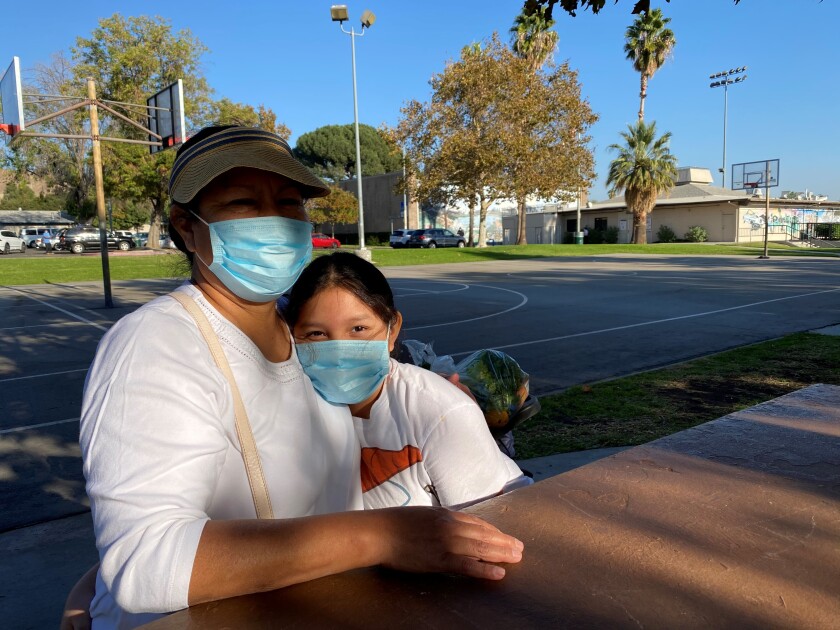

When they had their second food giveaway at the park last Thursday, the lines stretched around the block. Melba Martinez, 45, who is from Honduras, walked about three miles from her apartment in Pacoima with her 12-year-old daughter, Daniela, to pick up food. Martinez lost her job cleaning houses in Burbank and Glendale in March when the pandemic first started to bear down in Southern California. That work paid her about $2,000 a month.

Since then, Martinez has fallen behind on her monthly $1,500 rent. She was forced to not only borrow money from her sister to make rent, but also depend on church food distribution sites to feed her two children.

Melba Martinez, 45, and her 12-year-old daughter, Daniela, sit on a picnic bench at Hubert H. Humphrey Memorial Park in Pacoima. Martinez, an immigrant from Honduras, said she lost her job cleaning houses in March and now relies on food distribution sites to feed her children and has had to borrow money from her sister to pay her $1,500 monthly rent.

(Ruben Vives / Los Angeles Times)

As Martinez sat on a picnic bench, her daughter sat next to her taking an online class. Daniela has struggled at school. Sometimes the internet service in their apartment goes out, she said.

“Her grades have gone down,” her mother said.

Before the pandemic, Daniela said she was getting straight A’s.

“Now, I’m getting some A’s and a couple of Fs,” Daniela said. “One of the [Fs] is in history.”

Martinez said she lives in a state of constant worry. Back home in Honduras, one of the most destructive hurricanes in recent years displaced her brother and his family. She said the water rose so high they were forced to spend three days on a tree waiting for help.

Newsletter

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

She left her homeland for a better life. But now, it’s hard to imagine that goal has been accomplished. Martinez said the apartment building she lives in seems ripe for the spread of COVID-19. Many families live in cramped conditions, and she knows that some people have gotten infected.

“My neighbor upstairs lives with two other families and she told me one of the people who lives there got sick at the dealership where they work and came home and got everyone sick,” she said. “Downstairs from me are two families living in an apartment and they’ve all gotten infected.”

Martinez wonders whether the number of people who have the coronavirus is actually higher than people know. She said some people have made an earnest plea to her: “They’ve all told me, please don’t tell anyone that I got COVID-19.”

Times staff writers Rong-Gong Lin II, Ryan Menezes and Sean Greene contributed to this report.