Opening arguments in the trial over the killing of Ahmaud Arbery began on Friday morning in Brunswick, Ga., a community made uneasy this week by the selection of a nearly all-white jury to hear the case.

Three white men — Gregory McMichael, 65, a former police officer; Travis McMichael, his son, 35; and their neighbor William Bryan, 52 — are accused of killing Mr. Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man who was chased through a suburban neighborhood before being fatally shot by one of his pursuers in February 2020.

The jury, which is made up of residents from Glynn County, where more than a quarter of the population is Black, includes 11 white people and one Black person. Anxiety over the jury’s racial makeup was palpable among observers and participants as the jurors were being chosen.

Among those watching the proceedings in the courtroom were Wanda Cooper-Jones, Mr. Arbery’s mother; Marcus Arbery Sr., his father; and Leigh McMichael, Gregory McMichael’s wife.

Opening statements by the two sides will offer the clearest look in months at how the murder case against the three defendants will unfold. Each faces up to life in prison for his role in Mr. Arbery’s death.

The three men have distinct legal teams, each of which is expected to argue that the defendants were carrying out a legal citizen’s arrest under a state statute that has since been largely repealed. The men told the authorities that they suspected that Mr. Arbery had committed a series of break-ins in their neighborhood.

The prosecutors are likely to assert that the men had no right to make an arrest and that they should be held responsible for the death. Some observers have likened Mr. Arbery’s killing to a modern-day lynching.

Lawyers have said the trial could last a month. The extraordinarily long jury selection process, which includes the seating of four alternate jurors, has already underscored the explosive nature of this case, particularly in coastal Glynn County, where many of the 85,000 residents are connected by bonds of family, school or work, and where racial tension and harmony are deeply laced.

Inside the Glynn County Courthouse — a red brick building with imposing ionic columns fronting a park full of moss-covered oaks — lawyers spent days subjecting scores of potential jurors to intense rounds of questions about how much they knew about the case, whether they had formed opinions about the defendants’ guilt and their preferred news sources and social media networks.

Linda Dunikoski, the lead prosecutor, said in court that she was hoping for jurors who were a “blank slate.” But the killing was one of the most notorious in South Georgia in decades, and many prospective jurors — the court system sent out 1,000 jury notices — said they had already formed opinions about it.

The lengthy process stood in stark contrast to the case of Kyle Rittenhouse, an 18-year-old who is now on trial in Wisconsin for the deaths of two men and the wounding of another in the aftermath of protests in August 2020 over a police shooting. It took one day to seat a jury for that trial.

The indictment handed up by the grand jury in Glynn County lists nine criminal counts against each of the three defendants in the killing of Ahmaud Arbery. For each count, they are charged individually and as “parties concerned in the commission of a crime.”

Taken together, the charges provide a number of different ways that the defendants, Gregory McMichael, Travis McMichael and William Bryan, could wind up facing life in prison if they are convicted.

Here are the charges in the order listed in the indictment:

Count 1

Malice murder

This crime is defined in Georgia law as causing a person’s death with deliberate intention, without considerable provocation, and “where all the circumstances of the killing show an abandoned and malignant heart.” It is punishable by death, or by life imprisonment with or without possibility of parole.

Counts 2, 3, 4 AND 5

Felony murder

This charge applies when a death is caused in the course of committing another felony, “irrespective of malice” — in other words, whether or not the killing was intentional and unprovoked.

The other felonies in this case are listed in Counts 6 through 9 of the indictment; one count of felony murder is linked to each. If prosecutors prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendants committed one or more of those crimes and also caused Mr. Arbery’s death in the process, the basis would be laid for a conviction for felony murder.

Like malice murder, felony murder is punishable by death, or by life imprisonment with or without possibility of parole.

Count 6

Aggravated assault

One way Georgia law defines this crime is as an assault using a deadly weapon. This count charges the three men with attacking Mr. Arbery with a 12-gauge shotgun. It is punishable by imprisonment of one to 20 years.

Count 7

Aggravated assault

Another way Georgia law defines this crime is as an assault using “any object, device, or instrument which, when used offensively against a person, is likely to or actually does result in serious bodily injury.” This count charges the defendants with using two pickup trucks to assault Mr. Arbery. It is punishable by imprisonment of one to 20 years.

Count 8

False imprisonment

This charge applies when a person without legal authority “arrests, confines, or detains” another person “in violation of the personal liberty” of that person. Specifically, the defendants are charged with using their pickup trucks to chase, confine and detain Mr. Arbery “without legal authority.”

False imprisonment is punishable by one to 10 years in prison.

Count 9

Criminal attempt to commit a felony

Georgia law defines criminal attempt as performing “any act which constitutes a substantial step” toward the intentional commission of a crime — in this case, the false imprisonment charged in Count 8. A defendant can be convicted either of completing a particular crime or of attempting it, but not both.

Because false imprisonment is a felony, attempting it is also a felony, punishable by half the attempted crime’s maximum sentence: in this case, one to five years in prison.

Even as he approved the selection of a nearly all-white jury this week to hear the murder case against three white men accused of killing Ahmaud Arbery, the presiding judge declared that there was an appearance of “intentional discrimination” at play.

But Judge Timothy R. Walmsley of Glynn County Superior Court also said that defense lawyers had presented legitimate reasons unrelated to race to justify unseating eight Black potential jurors. And that, he said, was enough for him to reject the prosecution’s effort to reseat them.

What may have seemed like convoluted logic to non-lawyers was actually the judge’s scrupulous adherence to a 35-year-old Supreme Court decision that was meant to remove racial bias from the jury selection process — but has come to be considered a failure by many legal scholars.

The guidelines established by that ruling were central to the intense legal fight that erupted in court late Wednesday over the racial composition of the jury in the trial of the three defendants. The argument raised fundamental questions about what it means to be a fair and impartial juror, particularly in a high-profile trial unfolding in a small, interconnected community where nearly everyone has opinions about the case.

Defense lawyers told Judge Walmsley there were important, race-neutral reasons to unseat several Black candidates for the jury. One man, they said, had played high school football with Mr. Arbery. Another told lawyers that “this whole case is about racism.”

But the fact that the jury will be composed of 11 white people and one Black person in a Deep South trial over the killing of a Black man has profoundly dismayed some local residents who already had concerns about whether the trial will be fair.

“This jury is like a black eye to those of us who have been here for generations, whose ancestors labored and toiled and set a foundation for this community,” said Delores Polite, a community activist and distant relative of Mr. Arbery, who was fatally shot last year after being chased by three men who suspected him of a series of break-ins.

More broadly, the racially lopsided jury, in a county that is about 27 percent Black and 64 percent white, underscores the enduring challenges that American courts face in applying what seems to be a simple constitutional principle: that equal justice “requires a criminal trial free of racial discrimination in the jury selection process,” as Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh put it in a ruling from 2019.

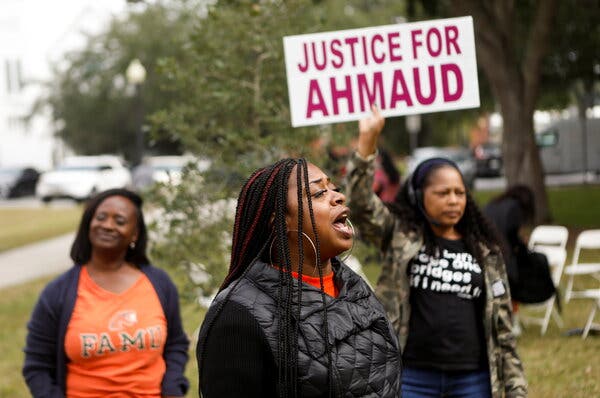

A group of clergy members gathered outside the Glynn County Superior Court in Brunswick, Ga., on Friday morning, urging the community to remain peaceful and united despite their unhappiness that a nearly all-white jury had been seated in the trial of the white men accused of killing Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man.

“We want to acknowledge that we hear and that we see your disappointment with some of the discoveries in the process of justice that have taken place,” said John Davis Perry II, a local minister. “Despite all of those disappointments, as faith leaders we stand together declaring to not forget that we serve a God who is not asleep.”

He added: “We want to encourage you to keep the faith and to continue to walk in the spirit of unity because God has promised that he will be with us through the process.”

Mr. Arbery’s aunt, Thea Brooks, said that having clergy members present had brought a measure of peace to the Arbery family and the Brunswick community.

Ms. Brooks said she anticipated that having to see the video of Mr. Arbery’s killing, which occurred on Feb. 23, 2020, would be especially difficult for her family. Mr. Arbery’s mother, who is in the courtroom, had not yet seen the video, she said.

But Ms. Brooks said she was ready for the trial to begin.

“It’s been almost two years that we’ve been here, we’ve been having to watch the video, hear the motions, go through preliminary hearings, in and out of court for motions and that takes a toll on you,” she said. “Now that we’re here, we just want this to be a smooth situation, get it done, get it over with, get justice served so we can move on and close this chapter of our lives.”

Judge Timothy R. Walmsley, who is presiding over the Ahmaud Arbery murder trial, ruled on a number of legal motions ahead of opening statements, including allowing into evidence video images from the body camera of a responding police officer who hovered over Mr. Arbery after he was shot.

Judge Walmsley also ruled against the defense’s request to bring a “use of force” expert into trial, and refused to allow into evidence a toxicology report showing that Mr. Arbery had THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, in his system when he died.

At one point, one of the lawyers representing Travis McMichael asked that certain portions of the body camera video not be played, because some of its content is inflammatory. The lawyer, Jason Sheffield, argued that the prosecution should use evidence “that is not going to incite the jury in a way.”

“I am asking the court to engage in a balancing test over whether or not that particular portion of the video needs to be played,” Mr. Sheffield said, bringing up photographs and testimony from the medical examiner and other witnesses that could also be used as evidence.

The lead prosecutor, Linda Dunikoski, argued in favor of using the body-cam video. “This is real, and to tell the jury ‘Oh, we’re not going to show you what really the results of pointing a shotgun at someone is,” she said, then interrupted herself to recount a sequence of events. “Travis McMichael left his house with a shotgun. Then he got out of his car, with the shotgun, and pointed it at this young man. And then he shot him with it.”

Judge Walmsley also denied a defense request to keep a photograph of Mr. Arbery, in a ball cap and polo shirt, from appearing in court.

“If there are more recent in-life photographs, then what would be the point of presenting one nine years ago?” argued Kevin Gough, a lawyer for William Bryan. “Other than to try to suggest to the jury that he was a jogger that day because he wears athletic clothing and a ball cap?”

After some back-and-forth with the defense over legal precedent, Judge Walmsley ruled, saying, “The court will permit the state’s use of that photograph that was described.”

On Friday morning, before the jury was seated, Judge Walmsley briefly ruled on two other motions in favor of the prosecution. One ruling denied the defense’s motion to block jurors from knowing that Travis McMichael’s pickup truck had a vanity decorative license plate with the old Georgia state flag on it. This flag incorporates in its design the Confederate battle flag.

Defense attorneys feared that prosecutors would bring up the flag — often interpreted as a symbol of racism — to argue that Mr. Arbery, who was being chased by Travis McMichael and his father, Greg McMichael, in the truck, would have seen the vanity plate and feared for his safety.

Judge Walmsley also granted prosecutors’ motion to prevent jurors from knowing that Mr. Arbery was on probation on the afternoon Feb. 23, 2020, when the three men chased him through their subdivision.