JERUSALEM — For a fleeting three days, it looked as if Israel had successfully rebooted its faulty fight against the coronavirus.

Then politics intervened.

In late July, a veteran Tel Aviv hospital administrator, Dr. Ronni Gamzu, was anointed the country’s virus czar and swept in with self-assurance. Acknowledging previous government mistakes, he enlisted the military to take responsibility for contact tracing and pleaded with Israelis to take the threat seriously and wear their masks.

He also vowed to restore the public’s trust, demanding accountability from municipal officials while replacing the central government’s ceaselessly zigzagging dictates with simple instructions that anyone, it seemed, should be able to understand and embrace.

Last Thursday, Dr. Gamzu won cabinet approval for a traffic light-themed plan to impose strict lockdowns on “red” cities with the worst outbreaks, while easing restrictions in “green” ones where the virus was finding fewer victims. The goal was to avoid, or at least delay, another economically strangling nationwide lockdown.

By Sunday, however, Dr. Gamzu was looking more like a victim himself.

Ultra-Orthodox leaders who felt that their community was being stigmatized revolted against the traffic light plan. This time, however, they did not bother to attack Dr. Gamzu, instead directing their ire at his most important backer, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

And Mr. Netanyahu, under fierce public pressure from one of his most vital constituencies, caved in on the targeted lockdown plan.

Forget about the harshest new restrictions in red cities, he announced Sunday night. Instead, he and Dr. Gamzu grasped at a watered-down nighttime curfew, something that Arab mayors had proposed to curtail big weddings but that even Dr. Gamzu later conceded would have little effect in ultra-Orthodox communities.

Mr. Netanyahu and Dr. Gamzu took turns at a microphone on Monday to project unity. Mr. Netanyahu insisted that he had not knuckled under but merely done what the professionals had recommended. Dr. Gamzu insisted that even if his professional recommendations had been blocked, he was determined to soldier on.

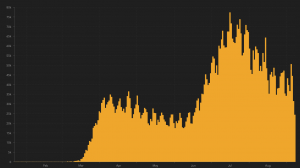

But the upshot for Israel is a bleak prospect: The pandemic has mushroomed, with Israel’s number of new cases near the worst in the world on a per-capita basis. Yet the odds of stopping its march seem slim as the Jewish High Holy Days approach.

Ordinarily, the New Year, Yom Kippur and Sukkot are a festive and unifying time. Instead, there are fears that by Sept. 18, when the holidays begin, Israel will be either overrun by the pandemic or under a full lockdown. And the deeply polarized country appears to be warring with itself along religious, cultural and political lines that may sound familiar to many Americans.

Secular Israeli Jews accuse the ultra-Orthodox and Arab citizens of spreading the virus in their overcrowded areas. The ultra-Orthodox point to the relative normalcy of life in Tel Aviv and complain that they are being singled out.

Joined by their right-wing allies, they ask why, if crowds are so dangerous, liberal-leaning protesters are allowed to gather by the thousands to demand Mr. Netanyahu’s ouster.

And a growing chorus of frustrated Israelis across the political spectrum accuse Mr. Netanyahu of working harder at holding onto power than on bringing infection rates down. Indeed, in dumping Dr. Gamzu’s lockdown plan, critics said Mr. Netanyahu had subverted his virus czar’s authority to mollify his ultra-Orthodox coalition partners.

“It shows that fighting the pandemic is not his first priority,” said Orit Galili-Zucker, a onetime Netanyahu strategist.

In effect, she said, the other crises that have weakened Mr. Netanyahu’s standing — his ongoing trial on corruption charges, and the anti-corruption demonstrations denouncing him — are inhibiting his willingness to let the professionals dictate how to combat the pandemic.

“The political story of Israel is affecting its fight against the virus,” Ms. Galili-Zucker said. “It’s very sad.”

Dr. Gamzu became Mr. Netanyahu’s virus czar after pioneering a program to protect the elderly from the virus at Ichilov Hospital in Tel Aviv. He addressed the Israeli public energetically and emotionally in frequent television appearances and Facebook videos, asserting that he would now make the decisions.

Others had refused the job because its powers were undefined. But Dr. Gamzu, exuding confidence, tried to turn that to his advantage.

“I have a natural authority,” he said on Aug. 31, at the start of an interview that took three days to complete because of repeated urgent interruptions. “I was director-general of the Ministry of Health, I know all the politicians, I know all the ministers. I know all the cabinet. I know all the political issues. But I’m not a politician. I’m a professional,” he added.

“I would say that I have 100 percent authority,” Dr. Gamzu declared.

He laid out a three-pronged strategy: restoring public confidence; building the infrastructure needed — faster and more widespread testing and many more epidemiological investigators — to break the chain of contagion; and empowering local authorities.

His signature initiative was the traffic light plan. It would give mayors the tools they needed to respond quickly to new outbreaks, but also give them the inducement they would need — easing restrictions — to win public cooperation.

If it worked, he said, it could help delay another nationwide lockdown until the army’s contact tracers are ready for an expected resurgence of the virus in the fall.

The problem politically was that nearly all the red cities turned out to be either predominantly Arab or ultra-Orthodox. And every action affecting the ultra-Orthodox sector elicited fierce pushback.

After a public outcry over the planned arrival of 12,000 or more yeshiva students from abroad, Dr. Gamzu said, he whittled the number down to 4,000.

The Coronavirus Outbreak ›

Frequently Asked Questions

Updated September 4, 2020

-

What are the symptoms of coronavirus?

- In the beginning, the coronavirus seemed like it was primarily a respiratory illness — many patients had fever and chills, were weak and tired, and coughed a lot, though some people don’t show many symptoms at all. Those who seemed sickest had pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome and received supplemental oxygen. By now, doctors have identified many more symptoms and syndromes. In April, the C.D.C. added to the list of early signs sore throat, fever, chills and muscle aches. Gastrointestinal upset, such as diarrhea and nausea, has also been observed. Another telltale sign of infection may be a sudden, profound diminution of one’s sense of smell and taste. Teenagers and young adults in some cases have developed painful red and purple lesions on their fingers and toes — nicknamed “Covid toe” — but few other serious symptoms.

-

Why is it safer to spend time together outside?

- Outdoor gatherings lower risk because wind disperses viral droplets, and sunlight can kill some of the virus. Open spaces prevent the virus from building up in concentrated amounts and being inhaled, which can happen when infected people exhale in a confined space for long stretches of time, said Dr. Julian W. Tang, a virologist at the University of Leicester.

-

Why does standing six feet away from others help?

- The coronavirus spreads primarily through droplets from your mouth and nose, especially when you cough or sneeze. The C.D.C., one of the organizations using that measure, bases its recommendation of six feet on the idea that most large droplets that people expel when they cough or sneeze will fall to the ground within six feet. But six feet has never been a magic number that guarantees complete protection. Sneezes, for instance, can launch droplets a lot farther than six feet, according to a recent study. It’s a rule of thumb: You should be safest standing six feet apart outside, especially when it’s windy. But keep a mask on at all times, even when you think you’re far enough apart.

-

I have antibodies. Am I now immune?

- As of right now, that seems likely, for at least several months. There have been frightening accounts of people suffering what seems to be a second bout of Covid-19. But experts say these patients may have a drawn-out course of infection, with the virus taking a slow toll weeks to months after initial exposure. People infected with the coronavirus typically produce immune molecules called antibodies, which are protective proteins made in response to an infection. These antibodies may last in the body only two to three months, which may seem worrisome, but that’s perfectly normal after an acute infection subsides, said Dr. Michael Mina, an immunologist at Harvard University. It may be possible to get the coronavirus again, but it’s highly unlikely that it would be possible in a short window of time from initial infection or make people sicker the second time.

-

What are my rights if I am worried about going back to work?

- Employers have to provide a safe workplace with policies that protect everyone equally. And if one of your co-workers tests positive for the coronavirus, the C.D.C. has said that employers should tell their employees — without giving you the sick employee’s name — that they may have been exposed to the virus.

Dr. Gamzu also wrote to the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, and warned of potentially dire health consequences if tens of thousands of ultra-Orthodox were allowed to make an annual pilgrimage to Uman, the burial site of a revered 18th-century rabbi.

Ukraine closed its borders, and Dr. Gamzu was accused of exceeding his pay grade — and of fanning anti-Semitism, no less — by politicians including the coalition whip for Mr. Netanyahu’s own Likud party.

Then Dr. Gamzu offended a leading rabbi, Chaim Kanievsky, over what he later said was a misunderstanding about the testing of yeshiva students, for which he profusely apologized.

The lockdown plan was “the last straw,” said Israel Cohen, a political commentator at an ultra-Orthodox radio station.

“All these things together brought the situation almost to the breaking point between Netanyahu and the ultra-Orthodox public,” he said. “People who usually expressed support for Bibi were saying on social media: ‘Hey, what’s this? They’re putting us in a ghetto.’”

Dr. Gamzu’s authority seemed to erode in plain view last week.

It took until just before midnight on Aug. 31 for him to get the government to close schools in red cities the next morning, the first day of school. But the mayor of Beitar Illit, an ultra-Orthodox West Bank settlement, allowed his city’s schools to reopen anyway. On Wednesday, Dr. Gamzu drove there to personally enforce the closure.

But it was Sunday’s reversal by Mr. Netanyahu that prompted a chorus of calls by Dr. Gamzu’s supporters for him to resign in protest, and left some Israelis despairing over what they called a leadership vacuum.

“I don’t know how anyone can be considered in charge of the situation when they have no power at all,” said Gadi Wolfsfeld, a political scientist at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya. “Every decision is either whittled down or ignored. You can’t expect the public to listen to the government when the government looks like it doesn’t know what the hell they’re doing.”

Dr. Gamzu gamely tried to bounce back on Monday.

With a nationwide lockdown looking increasingly inevitable, he stressed the advantages of starting one over the holidays: It would do less damage to the economy, which slows down then anyway, and would prevent large family meals and other opportunities for the virus to spread.

He insisted that he still had Mr. Netanyahu’s support for his broader strategy. And he said he was no quitter, and accepted that Mr. Netanyahu was operating under political constraints.

“I can understand complexity,” Dr. Gamzu said. “I’m not the type of person who says, well, if I’m not getting 100 percent consent to everything I bring to the table, then it’s all or none.”

If ultra-Orthodox leaders are savoring a victory over Dr. Gamzu and his lockdowns, there is still the matter of the virus, coursing its way through their communities with little to stop it.

“Who did we defeat?” asked Mr. Cohen, the radio commentator. “In the end, we all have to look after ourselves.”