A weary election season draws to a close as we approach the end of the year and coming of winter.

Chill laces the wind and darkness comes early each night.

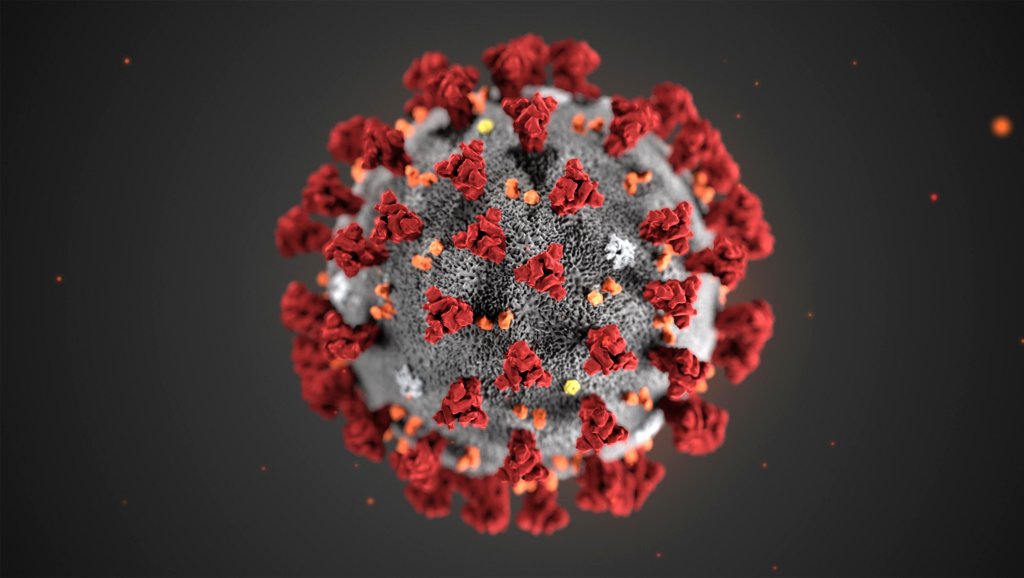

And across the country we see infection numbers spiking and hospitals and ICUs being strained to the seams, with executives invoking terms like “rationing of care.” Public health officials, their voices nearly-hoarse from pleading, are begging everyone, again, to wear masks and stay distanced as temperatures fall.

Every bit as much the smoke that has veiled our California skies, the virus seeps into our every moment — haunting our waking and our dreams.

We count the cost of the pandemic in communities suddenly bereft of in-person companionship, schools emptied of their students, dreams of all kinds deferred, a yet unknown burden of long-term sequelae from the virus itself and, of course, most obviously, the now near 200,000 lives lost in the United States and nearing 1 million worldwide.

As an oncologist, I treat people facing death every day. In doing so, it has become clear that the nearness of death does not so much create meaning as reveal it. Those who approach dying with some forewarning often find their priorities clarified in a way that lays bare the things that really matter.

In addition, some cancer patients find that the suffering often entailed by chemotherapy and the advancing difficulties associated with serious disease can soften a hard heart and open a closed mind. Knowledge that life is finite reminds us that the miracles surrounding us as we go about our lives — a sunset, the smile of a child, a flower’s fragrance, the sweetness of fruit, the embrace of a loved one, the release of forgiveness, and the magic of music — gather additional luster when we stop long enough to take them fully in.

The greatest meaning of the pandemic will come if—in its invisible fright—it reminds us that we are all fellow travelers. Life is too short for any of us to accomplish the good of which we are capable. Even after that happy day when we will all line up (I hope!) for a vaccine, none of us knows when death will come. Nor do we know who around us may already be facing that frightening prospect.

All of us will die one day — the question is when, not if. Think of it this way: How differently would you treat a friend — or, more to the point, an enemy — you knew was dying? Would you be more merciful? Would you more readily offer the benefit of the doubt. Would compassion and grace more easily elevate your instincts and soften your words?

In a moment when all of us could catch the virus at any moment, we would do well to remember that the dying person is each of us and every person around us.

Life is short.

Kindness matters.

Let’s wear masks as a sign of compassion and care for each other as a mark of how the pandemic has made us better, kinder, and more whole.

Let’s let the world’s suffering soften us and bind us together when other forces seek to draw us apart.

We are all in this together; there is suffering needing succor everywhere we turn.

Dr. Tyler Johnson is Inpatient Oncology Service Director at Stanford Hospital.