The first time a China-backed candidate was named Director General of the World Health Organization, the president of the United States had other things on his mind. China had just a few years earlier botched its response to the outbreak of a flu-like disease, first covering it up and then underreporting the results. No matter. The president wanted stable relations with Beijing, and no one in his administration raised any particular objections to the selection for the top job at the WHO.

On November 9, 2006, Dr. Margaret Chan, a physician from Hong Kong, was appointed to her first five year term, having garnered majority of support from the World Health Association—the nations who vote on top appointments to the WHO. Just two days earlier, George W. Bush’s Republican party had been hammered in midterm elections, losing both houses of Congress for the time since 1992. The Iraq war was heading south quickly, and in response Bush threw controversial Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld over the side, an acknowledgment that Iraq was a debacle. Who was going to run the WHO? In Washington the answer was simple: who cares?

The same was true five years later, when the Obama administration stood by as the pro-Beijing Chan—who appointed a slew of pro-Beijing bureaucrats during her tenure—was reappointed to another term. And when Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the now-controversial WHO director general, stood for election in the spring of 2017, the Trump administration paid little mind. Trump’s agenda when it came to China, as he had made clear during the 2016 campaign, was all about trade. “No one was particularly focused on [the WHO] at the time,” says a National Security Council staffer not authorized to speak on the record.

Tedros, an Ethiopian strongly backed by Beijing, easily won the directorship. The first non-physician ever elected to the post, he defeated David Nabarro of the UK, who had been nominally supported by Washington, 133 votes to 50 on the final ballot. The New York Times ran a bland story focusing on the fact that Tedros was the first African ever to become the WHO’s director.

China’s dissembling and opacity about the COVID-19 outbreak in the huge, central city of Wuhan—aided and abetted by the WHO in the critical early stages of the outbreak—is a scandal whose reverberations will be felt for years. As former Food and Drug Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said over the weekend, “There is some evidence to suggest that as late as January 20, Chinese officials were still saying there was no human-to-human transmission of the virus, and the WHO was validating those claims [as late as] January 14, sort of enabling the obfuscation from China.”

On Monday evening, Trump made it clear the era of Washington’s indifference to the WHO is over. He announced that U.S. funding of the organization will stop for a period of 60 to 90 days “while a review is conducted to assess the WHO’s role in severely mismanaging and covering up the spread of the coronavirus.” The administration wants to know: what did the WHO know, when did it know it, and what did Beijing tell it?

The move will be controversial, given the optics of cutting off funding to the world’s primary public health agency in the midst of a pandemic. But the WHO does have questions to answer, particularly as to when it really knew when the virus was spread human to human. On December 31, the government of Taiwan, which China blocks from being a member of the the WHO because it regards Taipei as a renegade province, got in touch with WHO to say that the mysterious disease in Wuhan bore similarities to SARS, the disease that China tried to cover up in 2003. SARS, like COVID-19, was transmissible human to human.

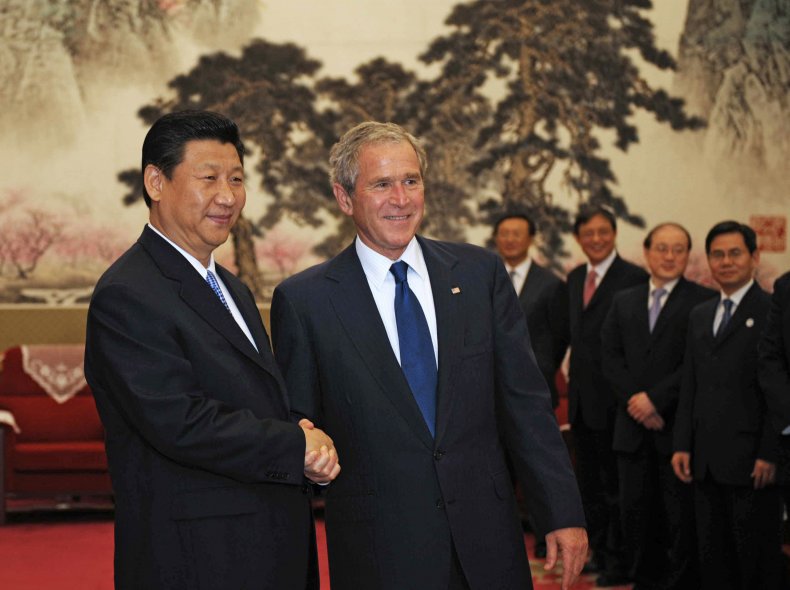

US President George W. Bush shakes hands with Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping (L) during a meeting in the Zhongnanhai compound in Beijing on August 10, 2008. Bush, who attended the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games on August 8, attended a church service in Beijing on August 10, using the occasion to drive home his message that China’s communist leaders have nothing to fear from religious faith. MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images

US President George W. Bush shakes hands with Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping (L) during a meeting in the Zhongnanhai compound in Beijing on August 10, 2008. Bush, who attended the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games on August 8, attended a church service in Beijing on August 10, using the occasion to drive home his message that China’s communist leaders have nothing to fear from religious faith. MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty ImagesLess well understood in this debacle is the role that the United States, and its allies in the developed world, played in allowing Beijing to become so influential in the organization, with consequences that now appear to be ruinous. The coronavirus catastrophe is the second massive “China shock” to hit the United States and the rest of developed world in the last 20 years. The first unfolded in slow motion, in the years after Beijing, with the U.S’s enthusiastic support, joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. What followed over the next decade and a half was, in the words of a landmark 2016 study by three U.S. economists for the National Bureau of Economic Research, “an epochal shift in patterns of world trade.”

In industry after industry—including, we now learn, the pharmaceutical and medical equipment industry— large companies shifted their supply chains out of the United States and into China, lured by the extraordinarily plentiful and cheap labor available there. Entire industries were hollowed out, and in the Rust Belt in particular, entire towns were devastated.

The bet that the U.S. political and economic establishments made was straightforward: that as China prospered, its authoritarian style of government would mellow, someday perhaps going the way of South Korea or Taiwan and embracing democracy. The costs imposed on blue collar, working class America would thus, in this view, be worth it.

The way successive U.S. administrations, first Bill Clinton’s, then Bush’s and Obama’s, dealt with China was fundamentally rooted in that hope. Clinton, in his last month in office, managed to get Congress to extend “permanent normal trade relations” to China, a critical step on the way to WTO membership. The next year China joined the WTO, and the Chinese economic miracle was jump-started. Obama’s Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner’s views on economic engagement were little different than those of his predecessor, former Goldman Sachs CEO Hank Paulson. That was fine with Obama, particularly during his first term.

Obama’s priority vis-a-vis Beijing was climate change. China’s explosive economic growth had made it the world’s largest emitter of CO2 into the atmosphere. If the Paris accord were to have any credibility, he had to have Beijing as a signatory. On April 1, 2016, he got his wish, when Beijing and Washington issued a joint statement saying they would both join the accord.

Obama aides such as Ben Rhodes, who was his deputy national security adviser, acknowledge that during his second term, Obama soured on Beijing. It had done little to live up to promises made that to rein in intellectual property theft, among other trade problems. The Obama administration ultimately filed 16 WTO complaints against China—an average of two a year while in office—but damage had been done. The last WTO suit it filed in January of 2017, Obama’s last month in office, was on behalf of the U.S. aluminum industry, which argued that Beijing was illegally subsidizing Chinese exports. When Obama entered office in January 2009 there were 14 active aluminum smelters operating in the U.S. Eight years later, there were five.

The overarching diplomatic strategy toward Beijing for both Obama and Bush was “strategic engagement.” That meant allowing China to gain more clout in international institutions such as the WHO. The thinking was that Beijing’s economic rise merited those rewards. But more important, the influence would help Beijing immerse itself into existing institutions, allowing it to grow into a “responsible global stakeholder,” as former Bush administration trade representative Robert Zoellick famously called it.

China’s President XI Jinping and US President Barack Obama hold a meeting during an official State Visit at the White House September 25, 2015 in Washington, DC. Chris Kleponis-Pool/Getty Images

China’s President XI Jinping and US President Barack Obama hold a meeting during an official State Visit at the White House September 25, 2015 in Washington, DC. Chris Kleponis-Pool/Getty ImagesThe U.S. and its allies would allow Chinese representatives—or allies of Beijing, like Tedros—to run organizations such as the WHO, the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Telecommunication Union, the Food and Agricultural Organization, and the U.N. Industrial Development Organization. They believed little harm could come of it. “It was benign neglect,” says Lanhee Chen, Director of Policy Studies at Stanford University’s public policy program. Some current and former U.S. officials believe Washington’s policy went well beyond benign neglect. Referring to China’s enhanced clout inside a variety of U.N agencies, including the WHO, Joseph Bosco, former China country director at the Pentagon says, “We encouraged it.”

The U.S. political and business establishment’s great China dream began to die with Xi Jinping’s ascension to the top political office in Beijing. His iron-fisted rule as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party makes the idea that China would soon follow in the democratic footsteps of Taiwan and South Korea seem farcical.

The second China ”shock”—the coronavirus-WHO-Beijing scandal—makes that obvious. It shows just how costly previous U.S. and allied assumptions about China can be. The belief that allowing Beijing to maneuver its favored candidate into the directorship of the WHO carried little risk was, arguably, a lethal misjudgment. If the WHO had insisted early on that Beijing share live strains of the virus with medical researchers in the outside world—and to date there is no evidence that it did—then a diagnostic test could have been developed much sooner, Gottlieb says. And had the Chinese “been more forthcoming about what was happening [in December] this might have been an entirely avoidable world event.”

The diplomatic fallout is just beginning. The cessation of funding, even if temporary, will get the WHO’s attention. The U.S. government’s annual contribution to the WHO is 22 percent of the total: more than double Beijing’s contribution. When you add in the massive amounts of money that philanthropic organizations like the Gates Foundation and pharmaceutical companies throw in—a sum far greater than Washington’s donation—the overall U.S. contribution is nearly ten times that of China.

Assuming U.S. funding restarts at some point, it would be wise to tailor the money with conditions, as Congress does in funding the U.N., suggests Stanford’s Chen. Start by insisting on far more transparency, public health officials say. The accounts of monthly board meetings published on the group’s website are cursory, says Chen. A summary of the December meeting, for example, simply says evidence of human-to-human transmission of COVID-19 in Wuhan was “insufficient.” The organization’s response in the past has been that more detailed accounts of its meetings would stifle scientific debate, but that argument doesn’t hold up. “It stands science on its head,” says Chen. ”The scientific method requires widespread dissemination of data and assumptions so they can be picked apart and improved. That’s the whole point.”

The U.S. and its allies will likely be unable to remove Tedros before his term ends in 2022, and Trump didn’t say he seeks his immediate ouster. But at the end of Tedros’s term, current and former diplomats and public health officials say, the U.S. must gather its allies and use its economic clout to install a new WHO director general who isn’t beholden to Beijing. “It will require old- fashioned horse-trading and lobbying and diplomacy, but it has to happen,” says Dan Blumenthal, Director of Asian Studies at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

He’ll get no argument from Trump administration officials, who hope they will still be around in 2022. In late January, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo—said by a White House official to be “fed up” with China—named career foreign service officer Mark Lambert to a newly created position: a special envoy whose job it is to counter China’s malign influence at the U.N. and other international agencies. He’ll have help. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe are both reported to be furious with Beijing and the WHO. Japan’s Deputy Prime Minister, Taro Aso, has said the WHO should change its name to the CHO: the China Health Organization.

There are two problems with the idea of pushing back on Beijing, one very real, the other potential. The first is, it will be hard to win over countries in the developing world that have become increasingly reliant on aid and trade with Beijing. The majority of Tedros’s votes in 2017 came from the developing world. The U.S., current and former diplomats say, needs to re-engage aggressively, diplomatically and economically, to claw back lost ground.

President Donald Trump is pictured during an appearance with China’s President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People on November 9, 2017 in Beijing, China. Thomas Peter-Pool/Getty Images

President Donald Trump is pictured during an appearance with China’s President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People on November 9, 2017 in Beijing, China. Thomas Peter-Pool/Getty ImagesThe second potential problem is U.S. politics: Trump right now trails former Vice President Joe Biden in most polls, and if the economy remains in a medically-induced recession throughout the year—more than a possibility—Biden is the likely winner. Beijing, based on Biden’s campaign to date, would breathe a sigh of relief. And so too would all those Fortune 500 executives who really don’t want to move their supply chains out of China. Biden has consistently downplayed Beijing as an economic and geopolitical rival throughout the campaign. His rhetoric is straight out of the 1990s. “China’s gonna eat our lunch?” he bellowed at one point on the trail. “C’mon, man…they’re not competition for us!”

Biden may be waking to reality. More than two months after the fact, his campaign quietly put out a statement saying that the former vice president actually supported Trump’s January decision to cut off air travel from China. (He had originally accused Trump of “xenophobia.”) The WHO’s handling of the coronavirus is the clearest indication to date of how dangerous a path Beijing was on: dangerous for the world. In the previous two decades, some leaders coddled China—in the eager hope it would grow to be just like us— while others genuflected to the soon-to-be-dominant power.

That era has come crashing to a close. Someone tell Joe Biden.