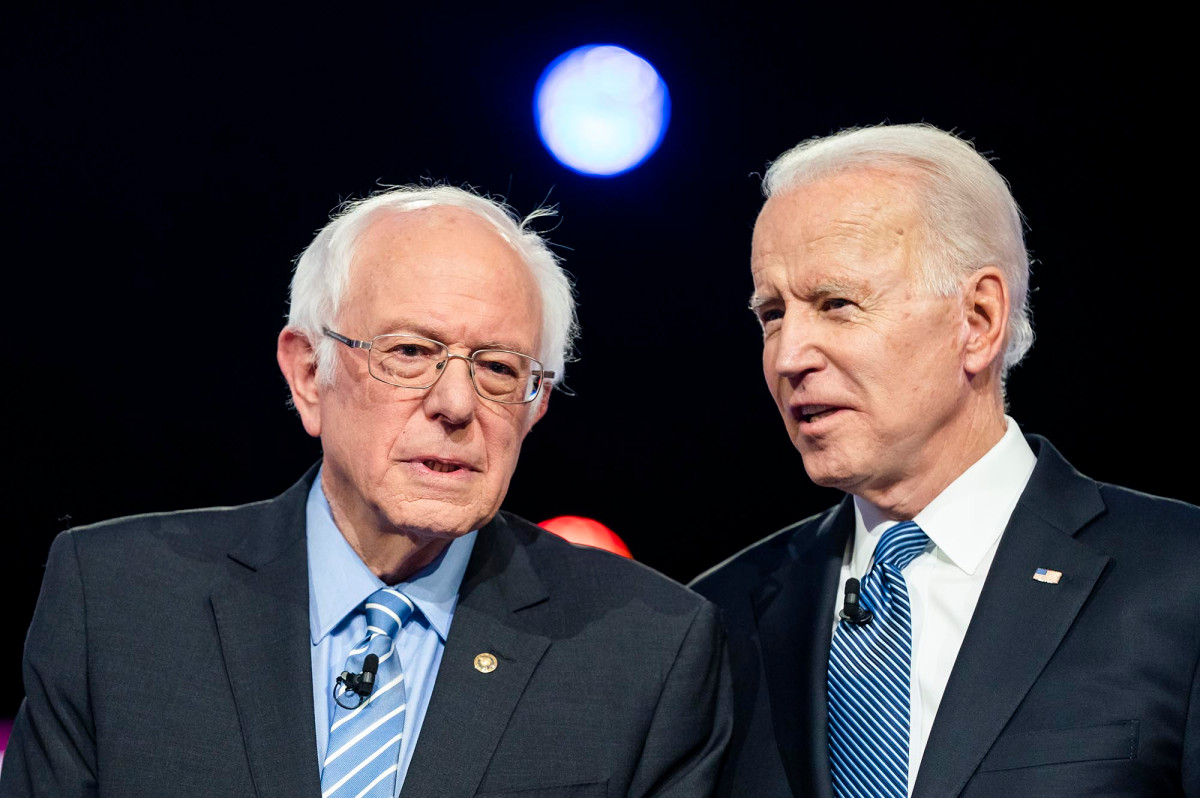

The world in which Bernie Sanders became a major political figure is no more. It ended with a speed almost as blinding as the celerity with which Joe Biden seized the momentum and the lead in the Democratic nominating process.

Feb. 29, when Biden won the South Carolina primary by 29 points, was only 40 days ago. But every political calculation Democratic primary voters were making there and in the four states that preceded it now seems positively quaint, like watching a flickering silent movie in a theater playing “Avengers: Endgame.”

Sanders confirmed as much on Wednesday by suspending his campaign and effectively handing the party’s nomination to Biden.

It isn’t just that the ex-veep has a nearly insurmountable delegate lead or that the logistics of voting in the remaining 19 primary states are so fiendishly difficult there’s little point in continuing a long-shot bid.

It’s that the subject Sanders has hammered home with metronomic monotony for the better part of a decade — the promise of a revolution that has undergirded his two presidential candidacies and his unstoppable fundraising machine — just doesn’t matter right now.

We have deliberately chosen to sink ourselves into a severe recession to combat an entity that can’t be blamed for its greed or taxed into submission. The virus can’t be yelled at, and, alas, for him, yelling at things is Sanders’ political métier.

He is a politician with a ready villain. That villain’s name isn’t President Trump. It is capitalism. And nothing in Sanders’ philosophy can account for the fact that capitalism is effectively shutting itself down for a while to save lives.

Sanders is a socialist. Socialism is about bringing a new world into being. One of its earliest theoreticians, Charles Fourier, believed that if socialism became the governing philosophy of the world, things would be so galactically harmonious that the oceans would turn to lemonade.

What Sanders and Fourier have in common is they prefer to traffic in fantasies rather than provide realistic and workable solutions to glaring and inescapable realities.

Who among us hasn’t noodled on what it would mean to win the lottery, to consider what you would do to fix things if you had unlimited money and power and were unconstrained by tradition or precedent or reality?

That is the seduction of socialism — it monopolizes resources and power and then distributes the goodies. But resources don’t work like that; if you seize them and centralize them, you pull them from their roots, and they begin to die.

Power can work like that, however, which is why socialism so often descends into totalitarianism. Sanders’ qualified enthusiasm for the socialist regimes in Cuba, Nicaragua, the Soviet Union and Venezuela is a sterling example of mistaking the dreamy rhetoric of progressive change for the destructive reality of what George Orwell described as “a boot stamping on a human face — forever.”

At a time of unprecedented crisis, our ability to avoid discomfiting reality and retreat into comforting fantasy is challenged at every moment. So it was with the entire purpose of Sanders’ campaign.

Estimates pegged the cost of the Sanders economic plan at $60 trillion over 10 years. In January, former Democratic Treasury Secretary Larry Summers said, “This is far more radical than all previous presidencies, on either the right or the left. The Sanders spending increase is roughly 2.5 times the size of the New Deal.”

Unlike Elizabeth Warren, who wrecked her own candidacy in part this way, Sanders never felt compelled to defend the price tag of his proposals — because he never put a price tag on them himself.

But as preposterous as the idea of increasing federal spending in this fashion was in January, it has now achieved a positively science-fictional status in the wake of the necessary federal response to the virus.

A government already $20 trillion in debt just increased its debt liability by as much as one-third in one fell swoop as part of the effort to stave off a global economic disaster on the scale of the Great Depression — and will almost certainly have to go back to the well one or two more times as the months pass.

The issue for our leaders going forward is how on earth we are going to get out of this fallout shelter we’ve constructed for ourselves and achieve some kind of financial stability afterward. Whatever the world is going to look like once this is over, it won’t be a world that will have time for the ludicrous lemonade delusions of Bernie Sanders.