Daavion Lee sported a Kelly green cap and gown, and his cousin Daniyah Bennett wore the black regalia from her middle school. They stood in the back of a pickup truck with an organizer of a march against police brutality and racism.

“These two have graduated, and they are the future of our community,” the organizer yelled into a megaphone. The graduates lifted their balled fists in the air, and the crowd erupted.

Just hours earlier on Saturday in Milwaukee, Ms. Bennett, 15, and Mr. Lee, 18, had finished their virtual graduation ceremonies. Now they were at their first protest.

For over two weeks, protests have cropped up in small towns and in large cities across the nation and around the world. The killing of George Floyd — who died after a Minneapolis police officer pressed his knee on Mr. Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes 46 seconds — set off the social unrest.

Canceled graduations, closed businesses and job losses caused by the coronavirus pandemic have fueled protesters and given students the time to participate, sometimes draped in their unused caps and gowns. Their photos from the protests make for powerful imagery that they hope conveys how they feel: that they should not inherit the same discrimination that their grandparents faced.

“My great-great-grandma was a slave,” Mr. Lee said. “I understand why my mom is still protesting about this.”

Mr. Lee graduated from Alexander Hamilton High School and Ms. Bennett from the Garland Elementary School, both in Milwaukee. They were both excited about reaching their milestones, but that joy was eclipsed by their need to stand up for what they believe in.

“I thought everyone should see that everyone can graduate, no matter the color of your skin,” said Mr. Lee, who will take a test to join the Army in June. “It’s scary as a black man just living in a world of chaos where people treat other people wrong because of their skin. They don’t understand us behind it.”

Outbursts of violence, fires and looting have occurred during some protests, which is why Mr. Lee’s mother initially did not want him to attend one after his graduation.

“I understand that they think that the protests are going to get out of hand,” Mr. Lee said. “If other people could live in someone else’s skin or shoes and see how they feel and how they are treated, then they will understand why people protested.”

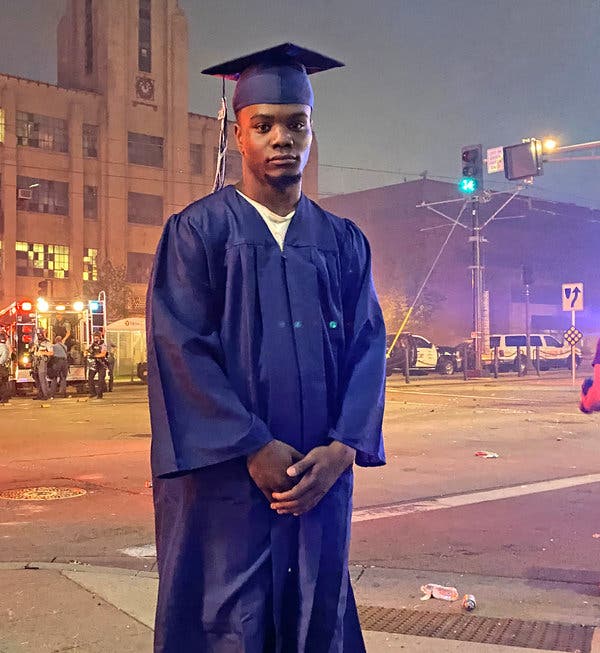

Deveonte Joseph, 17, posed in his royal blue cap and gown, bluejeans and icy white sneakers during a Minneapolis protest after graduating from Community of Peace Academy in St. Paul, Minn. In the photo, Mr. Joseph stands in the foreground while police officers in gas masks appear behind him. The officers congratulated him on his graduation, he said.

“That scene right there is history,” Mr. Joseph said.

He is the first boy out of his nine siblings to graduate from high school. Mr. Joseph wants to go to art school, but his family cannot afford it.

The marches have revealed, to many, the expansive inequalities in America that black and brown people in the United States contend with daily.

Black Americans face income gaps with their white counterparts, lower wages, lower college graduation rates and lower high school graduation rates.

Police violence usually affects black and brown people disproportionately. Officers who are caught — sometimes on video — beating or killing people unjustifiably are rarely punished.

“With everything going on in America, there is so much systematic change that has to happen,” said I’ziae Frazier, 18, who graduated from the Vicenza American High School in Italy on Saturday.

After her virtual graduation ceremony, Ms. Frazier went straight to the Piazza dei Signori, where a protest against police brutality and racism was underway.

“It is really frustrating what has been going on for centuries in America,” Ms. Frazier said. “I wanted to protest and speak to people and voice my opinion of why the system needs to change so badly. I feel the pain of my ancestors and my great-grandparents.”

Ms. Frazier, whose mother is in the Army, has lived in Italy for two years, but she spent most of her early teenage years in San Antonio. She plans to attend Howard University in the fall to study television and film.

At the protest in Italy, she saw signs that read “I Can’t Breathe” and “Black Lives Matter,” and one with Mr. Floyd’s face painted on it, she said. Excerpts from the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech played. Organizers also played the video of Mr. Floyd’s last moments on the Minneapolis pavement.

“It was hard to endure,” Ms. Frazier said. “I felt sick to my stomach. It was heart-wrenching because you knew it could be anyone. No one sees what we go through until it is on video and we have to be re-traumatized. How many times do we have to cry out for help?”

Black students feel an intense disappointment at the moment, said Monnica Williams, the Canada research chair for mental health disparities at the University of Ottawa’s School of Psychology.

“This gives them an opportunity to assert their independence and individuality in a way that they couldn’t for graduation,” Dr. Williams said. “There are so many stereotypes of black people of being unintelligent, and now they have the chance to go out and say, ‘I just graduated and I’m black and I am standing up against racism.’”

“I think it is a very proud thing for them,” she added. “They are using their success to push back.”

Tesia Walker, 17, was very proud to graduate but prouder to use her right to protest by heading to the streets of Los Angeles after she graduated from Palisades Charter High School.

“We are finding ways to exercise the rights that we do have,” Ms. Walker said. “Protesting is putting in my best efforts because I don’t really have a lot of money to donate, so I am doing the best I can.”

Ms. Walker is headed to Howard University in the fall to study to become a nurse. She hopes that the work she does makes the world a better place for future generations of black Americans.

“You always think someone else is going to do it, but as you go on living, you realize the problem isn’t solved,” Ms. Walker said. “It keeps recurring. It never ends. You have to do something yourself.”

“My generation realized we have to step out,” she said. “We are the future, and we have to make a change now if we are going to have a better future for our kids.”