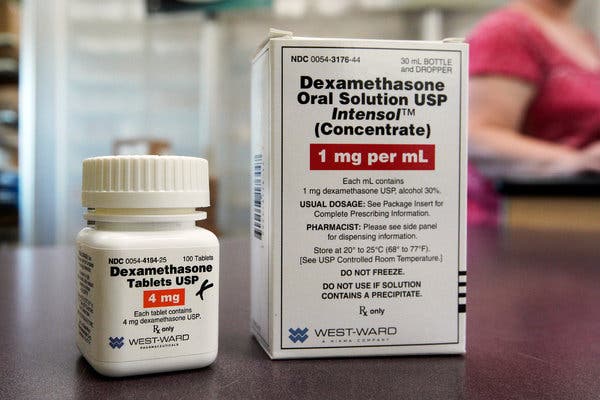

The recent news that a decades-old steroid drug, dexamethasone, showed a one-third reduction in mortality for patients with severe Covid-19 infections has generated immense hope in the medical community. The finding came from the Recovery trial, a large randomized controlled trial in Britain.

The reason doctors are so excited is that randomized controlled trials are the gold standard in medicine. Using randomization (by, say, flipping a coin to assign patients to a new treatment or not) is the best way to determine whether treatments work.

Unfortunately, randomized trials take time — which is a problem when doctors need answers now. So doctors and public health officials have been turning to available real-world data on patient outcomes and trying to make sense of them.

But it can be hard for doctors to find the answers they need in this observational data because without randomization, hidden biases can lead to misleading results. For example, if patients who receive a treatment tend to be sicker, we may incorrectly conclude that a treatment harms patients. Concerns over these biases have led several observational studies about Covid-19 treatments to be heavily criticized.

Do we need to wait for randomized trials to act? Not necessarily. The key lies in a set of tools economists have been using for decades: natural experiments.

With natural experiments, you can get around many of the hidden biases that plague observational studies by looking for circumstances that happen by chance — events that cause patients to be essentially randomized to one treatment or another. One study used a national shortage of the drug norepinephrine as a natural experiment to assess the drug’s effect on the mortality of patients critically ill with sepsis, comparing mortality rates of otherwise similar sepsis patients in the months before, during and after the shortage.

Although natural experiments are commonly used by economists, they’ve been infrequently used in medicine, where randomized trials have appropriately dominated.

“Large-scale randomized evaluations have been less common in economics, prioritizing the need for economists to identify often creative but sometimes narrow natural experiments to estimate the causal effects of treatments,” said Amitabh Chandra, an economist at the Harvard Business School and the Kennedy School of Government.

Ashish Jha, recently appointed the dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, said that while “natural experiments have causal interpretations, typical associational studies in medicine do not, which may make some medical researchers less comfortable interpreting the results.”

But randomized trials may not always be available. Or they may be too cumbersome to perform, or not ethical. Most doctors can relate to recent comments by the Food and Drug Administration director Stephen Hahn in last week’s congressional pandemic hearing. “In a rapidly moving situation like we have now with Covid-19,” he said, decisions are made “based on the data that’s available to us at the time.”

So, until the trials arrive, here are some ideas for how natural experiments could help:

Timing of treatment

Patients hospitalized with critically ill Covid-19 infection in the days before the Recovery trial results were announced would be expected to have worse outcomes than otherwise similar patients hospitalized in the days afterward, assuming doctors suddenly started using more dexamethasone (which they almost certainly have). Consistent with the trial results, we would expect to see an effect only in Covid-19 patients who were critically ill.

Based on the trial’s results, it’s also reasonable to think that once patients are critically ill, earlier treatment with dexamethasone might lead to better outcomes (the steroid has not been shown to be effective with patients who are not on respiratory support). This hypothesis could be tested by evaluating whether mortality rates were lower for patients hospitalized with severe Covid-19 infection in the one to two days before the Recovery announcement compared with otherwise similar patients hospitalized in the week prior — who would, by chance, be getting the drug later in their disease course.

Staggered changes in protocols

Changes over time in practice patterns within hospitals could also be used to better estimate the effectiveness of Covid-19 treatments. Hospitals have varied considerably in their treatment protocols for Covid-19, and these protocols have changed in the months since the pandemic began. The staggered change in treatment patterns across hospitals could allow researchers to estimate the effectiveness of Covid-19 treatments by using each hospital, at a different period in time, as its own control.

-

Frequently Asked Questions and Advice

Updated June 30, 2020

-

What are the symptoms of coronavirus?

Common symptoms include fever, a dry cough, fatigue and difficulty breathing or shortness of breath. Some of these symptoms overlap with those of the flu, making detection difficult, but runny noses and stuffy sinuses are less common. The C.D.C. has also added chills, muscle pain, sore throat, headache and a new loss of the sense of taste or smell as symptoms to look out for. Most people fall ill five to seven days after exposure, but symptoms may appear in as few as two days or as many as 14 days.

-

What’s the best material for a mask?

Scientists around the country have tried to identify everyday materials that do a good job of filtering microscopic particles. In recent tests, HEPA furnace filters scored high, as did vacuum cleaner bags, fabric similar to flannel pajamas and those of 600-count pillowcases. Other materials tested included layered coffee filters and scarves and bandannas. These scored lower, but still captured a small percentage of particles.

-

Is it harder to exercise while wearing a mask?

A commentary published this month on the website of the British Journal of Sports Medicine points out that covering your face during exercise “comes with issues of potential breathing restriction and discomfort” and requires “balancing benefits versus possible adverse events.” Masks do alter exercise, says Cedric X. Bryant, the president and chief science officer of the American Council on Exercise, a nonprofit organization that funds exercise research and certifies fitness professionals. “In my personal experience,” he says, “heart rates are higher at the same relative intensity when you wear a mask.” Some people also could experience lightheadedness during familiar workouts while masked, says Len Kravitz, a professor of exercise science at the University of New Mexico.

-

I’ve heard about a treatment called dexamethasone. Does it work?

The steroid, dexamethasone, is the first treatment shown to reduce mortality in severely ill patients, according to scientists in Britain. The drug appears to reduce inflammation caused by the immune system, protecting the tissues. In the study, dexamethasone reduced deaths of patients on ventilators by one-third, and deaths of patients on oxygen by one-fifth.

-

What is pandemic paid leave?

The coronavirus emergency relief package gives many American workers paid leave if they need to take time off because of the virus. It gives qualified workers two weeks of paid sick leave if they are ill, quarantined or seeking diagnosis or preventive care for coronavirus, or if they are caring for sick family members. It gives 12 weeks of paid leave to people caring for children whose schools are closed or whose child care provider is unavailable because of the coronavirus. It is the first time the United States has had widespread federally mandated paid leave, and includes people who don’t typically get such benefits, like part-time and gig economy workers. But the measure excludes at least half of private-sector workers, including those at the country’s largest employers, and gives small employers significant leeway to deny leave.

-

Does asymptomatic transmission of Covid-19 happen?

So far, the evidence seems to show it does. A widely cited paper published in April suggests that people are most infectious about two days before the onset of coronavirus symptoms and estimated that 44 percent of new infections were a result of transmission from people who were not yet showing symptoms. Recently, a top expert at the World Health Organization stated that transmission of the coronavirus by people who did not have symptoms was “very rare,” but she later walked back that statement.

-

What’s the risk of catching coronavirus from a surface?

Touching contaminated objects and then infecting ourselves with the germs is not typically how the virus spreads. But it can happen. A number of studies of flu, rhinovirus, coronavirus and other microbes have shown that respiratory illnesses, including the new coronavirus, can spread by touching contaminated surfaces, particularly in places like day care centers, offices and hospitals. But a long chain of events has to happen for the disease to spread that way. The best way to protect yourself from coronavirus — whether it’s surface transmission or close human contact — is still social distancing, washing your hands, not touching your face and wearing masks.

-

How does blood type influence coronavirus?

A study by European scientists is the first to document a strong statistical link between genetic variations and Covid-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus. Having Type A blood was linked to a 50 percent increase in the likelihood that a patient would need to get oxygen or to go on a ventilator, according to the new study.

-

How many people have lost their jobs due to coronavirus in the U.S.?

The unemployment rate fell to 13.3 percent in May, the Labor Department said on June 5, an unexpected improvement in the nation’s job market as hiring rebounded faster than economists expected. Economists had forecast the unemployment rate to increase to as much as 20 percent, after it hit 14.7 percent in April, which was the highest since the government began keeping official statistics after World War II. But the unemployment rate dipped instead, with employers adding 2.5 million jobs, after more than 20 million jobs were lost in April.

-

How can I protect myself while flying?

If air travel is unavoidable, there are some steps you can take to protect yourself. Most important: Wash your hands often, and stop touching your face. If possible, choose a window seat. A study from Emory University found that during flu season, the safest place to sit on a plane is by a window, as people sitting in window seats had less contact with potentially sick people. Disinfect hard surfaces. When you get to your seat and your hands are clean, use disinfecting wipes to clean the hard surfaces at your seat like the head and arm rest, the seatbelt buckle, the remote, screen, seat back pocket and the tray table. If the seat is hard and nonporous or leather or pleather, you can wipe that down, too. (Using wipes on upholstered seats could lead to a wet seat and spreading of germs rather than killing them.)

-

What should I do if I feel sick?

If you’ve been exposed to the coronavirus or think you have, and have a fever or symptoms like a cough or difficulty breathing, call a doctor. They should give you advice on whether you should be tested, how to get tested, and how to seek medical treatment without potentially infecting or exposing others.

-

For example, if dexamethasone is indeed effective, we would expect that hospitals that quickly incorporated the drug into treatment protocols after the Recovery trial announcement would experience earlier reductions in Covid-19 deaths than hospitals adopting it later. The key to this natural experiment would be to verify that the average characteristics of coronavirus patients within a hospital would be unchanged in the short interval before protocols were changed versus afterward.

Just above or below a threshold

The sometimes-arbitrary thresholds that hospitals use to decide which patients receive specific treatments could be used to better estimate the effectiveness of Covid-19 treatments. Treatment decisions often rely on clinical cutoffs, such that patients immediately above or below a threshold have very different likelihoods of treatment despite being otherwise similar.

For example, if a hospital decides that every person needing more than six liters per minute of oxygen will go on a ventilator, patients using six liters will go on a ventilator, but those using five liters will not — even though they are much the same.

The receipt of treatment is therefore effectively random for those patients near the cutoff, something economists call a regression discontinuity. To the extent that hospital protocols specify thresholds above or below which a scarce treatment can be given, knowledge of these thresholds could be used to demonstrate whether differences in treatment around the threshold correspond to differences in clinical outcomes.

These are just a few ideas to demonstrate the types of questions we could be asking to avoid the common biases encountered when using observational data. But it’s important to remember that natural experiments are happening by accident all the time, and many have already happened — it’s just a matter of looking for them. Randomized trials will remain the gold standard in health care, but just because these methods may be new to some health researchers does not mean we shouldn’t be using them when trials either take too long or cannot be done at all.

Anupam B. Jena, M.D., Ph.D., is an economist, a physician, and the Ruth L. Newhouse Associate Professor at Harvard Medical School. Follow him on Twitter at @AnupamBJena. Christopher M. Worsham, M.D., is a pulmonologist and critical care physician at Harvard Medical School. Follow him on Twitter at @ChrisWorsham.