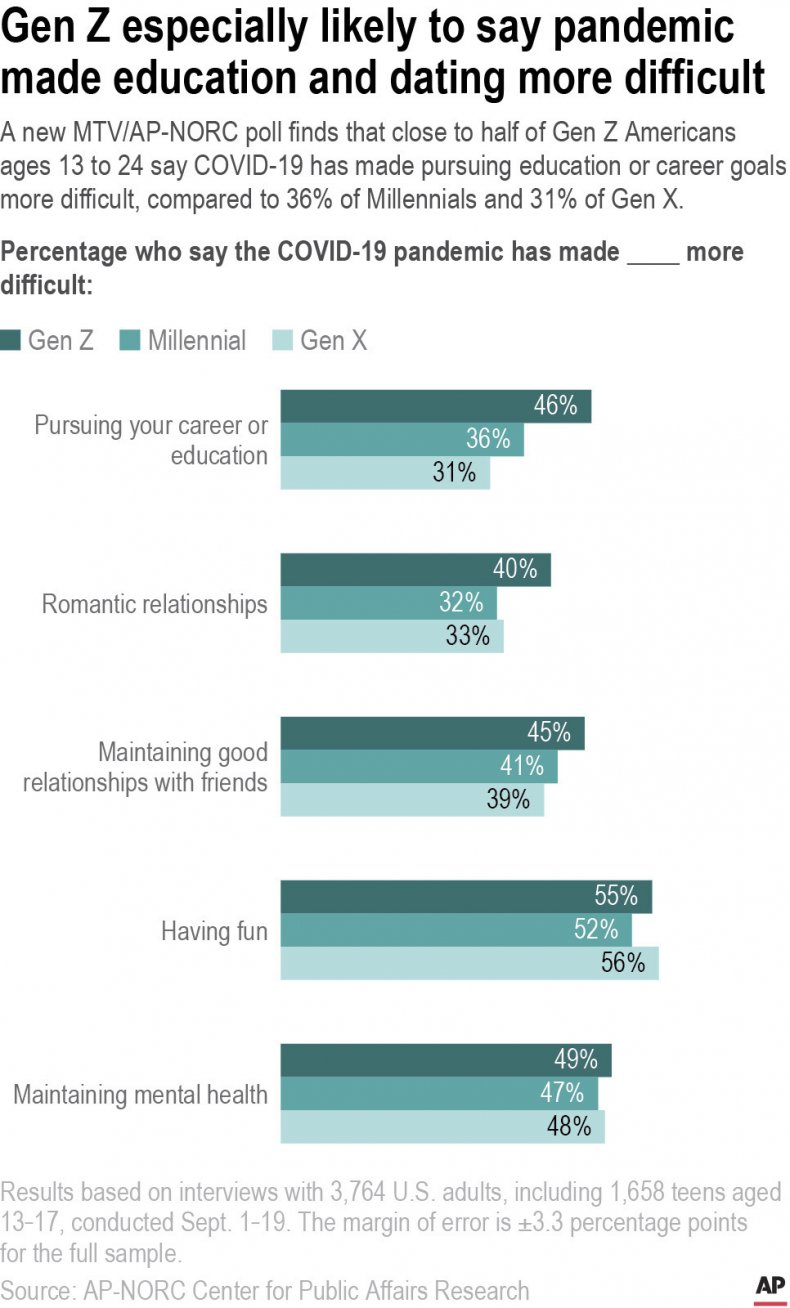

A recent poll found that the COVID-19 pandemic has been a stressor for many Americans, with the biggest toll taken on teens and young adults.

A survey from MTV Entertainment Group and The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research showed that over a third of Americans between the ages of 13 and 56 called the pandemic a “major source of stress.”

Especially strong stressors included fear of getting COVID-19 and uncertainty about the future.

Nearly half of the study’s participants, across all generations, said the pandemic made maintaining mental health more difficult. Just over half said it made having fun more difficult.

When looking specifically at Americans between the ages of 13 and 24, those numbers increase, with 55 percent saying the pandemic has made having fun more difficult.

According to the AP, Gen Z also reported more difficulty maintaining friendships, with 45 percent saying this compared to 39 percent of Generation X.

Another 46 percent reported difficulty with education and career goals. The survey found that about two-thirds of Gen Z saw education as “very” or “extremely” important to their identity, a jump from just half of Millennials and 4 in 10 Gen X.

Seattle Children’s Hospital pediatrician Dr. Cora Breuner told AP that the larger impact on younger people is linked to where they are in brain development.

“It’s this perfect storm where you have isolated learning, decreased social interaction with peers, and parents who also are struggling with similar issues,” Breuner said.

For more reporting from the Associated Press, see below.

Gene J. Puskar, File/AP Photo

The findings are consistent with what health and education experts are seeing. After months of remote schooling and limited social interaction, teens and young adults are reporting higher rates of depression and anxiety. Many are also coping with academic setbacks suffered during online schooling.

For 16-year-old Ivy Enyenihi, just thinking about last school year is hard. While her parents continued working in person, she spent day after day alone at their home in Knoxville, Tennessee. Her high school’s online classes included live interaction with a teacher just two days a week, leaving her totally isolated most days.

“I’m a very social person, and so not having people around was probably what made it the hardest,” Enyenihi said. “It just made normal things hard to do. And it definitely made me depressed.”

By the spring semester, she was skipping assignments and doing the bare minimum to get by. She felt cut off from the classmates and teachers at her school.

Things have improved since she returned to in-person classes this year, but she’s still catching up on math lessons she missed last year, and she wonders if she’s done enough to stand out on college applications. Overall, the sense of isolation has faded, but its memory lingers.

“It’s still a part of me,” she said. “If I think of it, it comes back up.”

Tanner Boggs, 21, says the pandemic has shaken up nearly every aspect of his life. The senior at the University of South Carolina says his academics, his mental health and his physical health all took hits.

He spent most of last school year in the bedroom of his apartment, with waning motivation to keep up with online classes. Some days he would wake up only to log into a Zoom lecture and then crawl back into bed. His anxieties worsened until tasks like going to the grocery store became unbearable.

He rarely went out but still ended up getting COVID-19 from a roommate, leaving him with symptoms that he still suffers from, he said.

After getting vaccinated and returning to in-person classes, his academics and mental health have improved. But some friendships seem to have faded, he said, and parts of his life are changed forever.

“The best I can describe it is tragic,” Boggs said. “It has affected every aspect of my life from relationships with friends and peers to the way I get groceries. Just everything.”

It’s no surprise that young people see education as a potential obstacle, said Vilmaris González, who manages youth programs for the nonprofit Education Trust in Tennessee. As many confront learning setbacks, they’re also emerging into a world where the future of work and higher education are as uncertain as ever, she said.

“I’m sure we won’t understand the gravity of those impacts for years to come,” she said. “This is going to mark their generation forever.”

For some, the pandemic has been a time to rethink future plans. Before, Gabi Hartinger, 21, was studying to become a teacher. But the last year brought life-changing turmoil—her father spent more than 40 days hospitalized with COVID-19, and her own isolation and anxiety led her to seek mental health counseling.

Now, Hartinger, a senior at the College of the Ozarks in Point Lookout, Missouri, hopes to become a school counselor to help younger students coping with their own challenges.

“For a lot of high schoolers I knew, school during the pandemic was a big struggle,” she said. “I think that that kind of changed my view on what I want to do when I get out of here.”

AP Photo