Of the 150-plus coronavirus vaccines in development around the world, the lion’s share will rely on a needle prick to make their way into the body.

Most vaccines throughout history have been jabbed into the upper arm, often to great success. But when protecting people against pathogens that invade the airway — like the coronavirus — an intramuscular shot isn’t necessarily the best strategy, some experts say.

“When we take apart and present pathogens in a way that the immune system doesn’t naturally see them, it’s not as ideal,” said Avery August, an immunologist at Cornell University. “You run the risk of not generating the right immune response.”

Many microbes, including the coronavirus, enter the body through the mucosa — wet, squishy tissues that line the nose, mouth, lungs and digestive tract — triggering a unique immune response from cells and molecules there. Intramuscular vaccines generally do a poor job of eliciting this mucosal response, and must instead rely on immune cells mobilized from elsewhere in the body flocking to the site of infection.

Given the potency and rapid spread of the coronavirus, some say it makes sense to develop vaccines for the airway as well as the more standard jabs. “Knowing how potent mucosal responses can be against a viral pathogen, it would be ideal to be thinking about mucosal vaccines,” said Akiko Iwasaki, an immunologist at Yale University.

Several research groups, including teams in the United States, Canada and the Netherlands, are working on nasal coronavirus vaccines. And a few companies, including the American biotech Vaxart, are starting to cook up oral formulations, which deliver their contents to another mucus-rich surface: the spongy lining of the gut.

The hope is that mucosal vaccines will do all that their intramuscular competitors can and more, mounting a multipronged attack on the coronavirus from the moment it tries to breach the body’s barriers, said Deepta Bhattacharya, an immunologist at the University of Arizona.

Under ideal circumstances, both types of vaccines would marshal a response in the blood. B cells, for example, would churn out antibodies — including a particularly potent disease-fighter called IgG — to roam the body in search of invaders to dispatch. Other cells, called T cells, would either help B cells produce antibodies or seek out and destroy infected cells.

But vaccines spritzed through the nose or mouth would also tap into another set of immune cells that hang around mucosal tissues. The B cells that reside here can make another type of antibody, called IgA, that plays a large role in bringing gut and airway pathogens to heel. And T cells in this neighborhood can memorize the features of specific pathogens, then spend the rest of their lives patrolling the places they first encountered them.

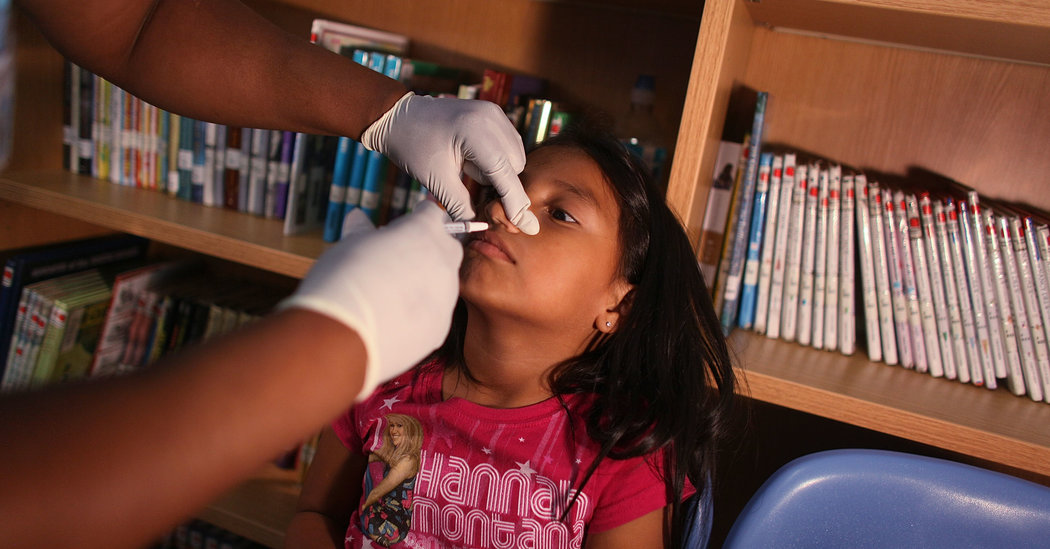

These mucosal immune responses seem to underlie the success of the oral polio vaccine, which contains a weakened form of polio virus and has helped most of the world eradicate polio. When it debuted in the 1960s, the vaccine was considered, in many ways, an enormous improvement over its injected predecessor because it targeted the body’s immune response in the gut, where the virus thrives. Many people who took the oral vaccine seemed to quash infections even before they felt symptoms — or passed the germ on to others.

“It was a fabulous vaccine to stop the transmission of polio,” said Dr. Anna Durbin, a vaccine expert at Johns Hopkins University. “It helped induce herd immunity,” she said, referring to the threshold of the population that needs to be immune to a pathogen to keep it from spreading.

Vaccines given through muscle are great for prompting the body to churn out antibodies in the bloodstream, like IgG. If a pathogen shows up, hordes of these on-call molecules will rush to meet it.

For many respiratory infections, that’s good enough.

“The majority of respiratory vaccines, like the measles vaccine, are given intramuscularly, and it works,” Dr. Iwasaki said. “If enough antibodies reach the right mucosal surface, it doesn’t really matter how they were induced.”

Still, relying on that strategy alone can be risky — a bit like shoring up a bank’s security at every entrance except for the one a thief would most likely hit. Sentinels roving throughout the building could subdue the interloper after they trip the alarm. But by that point, some damage has probably already been done.

-

Frequently Asked Questions

Updated July 7, 2020

-

Is the coronavirus airborne?

The coronavirus can stay aloft for hours in tiny droplets in stagnant air, infecting people as they inhale, mounting scientific evidence suggests. This risk is highest in crowded indoor spaces with poor ventilation, and may help explain super-spreading events reported in meatpacking plants, churches and restaurants. It’s unclear how often the virus is spread via these tiny droplets, or aerosols, compared with larger droplets that are expelled when a sick person coughs or sneezes, or transmitted through contact with contaminated surfaces, said Linsey Marr, an aerosol expert at Virginia Tech. Aerosols are released even when a person without symptoms exhales, talks or sings, according to Dr. Marr and more than 200 other experts, who have outlined the evidence in an open letter to the World Health Organization.

-

What are the symptoms of coronavirus?

Common symptoms include fever, a dry cough, fatigue and difficulty breathing or shortness of breath. Some of these symptoms overlap with those of the flu, making detection difficult, but runny noses and stuffy sinuses are less common. The C.D.C. has also added chills, muscle pain, sore throat, headache and a new loss of the sense of taste or smell as symptoms to look out for. Most people fall ill five to seven days after exposure, but symptoms may appear in as few as two days or as many as 14 days.

-

What’s the best material for a mask?

Scientists around the country have tried to identify everyday materials that do a good job of filtering microscopic particles. In recent tests, HEPA furnace filters scored high, as did vacuum cleaner bags, fabric similar to flannel pajamas and those of 600-count pillowcases. Other materials tested included layered coffee filters and scarves and bandannas. These scored lower, but still captured a small percentage of particles.

-

Is it harder to exercise while wearing a mask?

A commentary published this month on the website of the British Journal of Sports Medicine points out that covering your face during exercise “comes with issues of potential breathing restriction and discomfort” and requires “balancing benefits versus possible adverse events.” Masks do alter exercise, says Cedric X. Bryant, the president and chief science officer of the American Council on Exercise, a nonprofit organization that funds exercise research and certifies fitness professionals. “In my personal experience,” he says, “heart rates are higher at the same relative intensity when you wear a mask.” Some people also could experience lightheadedness during familiar workouts while masked, says Len Kravitz, a professor of exercise science at the University of New Mexico.

-

I’ve heard about a treatment called dexamethasone. Does it work?

The steroid, dexamethasone, is the first treatment shown to reduce mortality in severely ill patients, according to scientists in Britain. The drug appears to reduce inflammation caused by the immune system, protecting the tissues. In the study, dexamethasone reduced deaths of patients on ventilators by one-third, and deaths of patients on oxygen by one-fifth.

-

What is pandemic paid leave?

The coronavirus emergency relief package gives many American workers paid leave if they need to take time off because of the virus. It gives qualified workers two weeks of paid sick leave if they are ill, quarantined or seeking diagnosis or preventive care for coronavirus, or if they are caring for sick family members. It gives 12 weeks of paid leave to people caring for children whose schools are closed or whose child care provider is unavailable because of the coronavirus. It is the first time the United States has had widespread federally mandated paid leave, and includes people who don’t typically get such benefits, like part-time and gig economy workers. But the measure excludes at least half of private-sector workers, including those at the country’s largest employers, and gives small employers significant leeway to deny leave.

-

Does asymptomatic transmission of Covid-19 happen?

So far, the evidence seems to show it does. A widely cited paper published in April suggests that people are most infectious about two days before the onset of coronavirus symptoms and estimated that 44 percent of new infections were a result of transmission from people who were not yet showing symptoms. Recently, a top expert at the World Health Organization stated that transmission of the coronavirus by people who did not have symptoms was “very rare,” but she later walked back that statement.

-

What’s the risk of catching coronavirus from a surface?

Touching contaminated objects and then infecting ourselves with the germs is not typically how the virus spreads. But it can happen. A number of studies of flu, rhinovirus, coronavirus and other microbes have shown that respiratory illnesses, including the new coronavirus, can spread by touching contaminated surfaces, particularly in places like day care centers, offices and hospitals. But a long chain of events has to happen for the disease to spread that way. The best way to protect yourself from coronavirus — whether it’s surface transmission or close human contact — is still social distancing, washing your hands, not touching your face and wearing masks.

-

How does blood type influence coronavirus?

A study by European scientists is the first to document a strong statistical link between genetic variations and Covid-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus. Having Type A blood was linked to a 50 percent increase in the likelihood that a patient would need to get oxygen or to go on a ventilator, according to the new study.

-

How can I protect myself while flying?

If air travel is unavoidable, there are some steps you can take to protect yourself. Most important: Wash your hands often, and stop touching your face. If possible, choose a window seat. A study from Emory University found that during flu season, the safest place to sit on a plane is by a window, as people sitting in window seats had less contact with potentially sick people. Disinfect hard surfaces. When you get to your seat and your hands are clean, use disinfecting wipes to clean the hard surfaces at your seat like the head and arm rest, the seatbelt buckle, the remote, screen, seat back pocket and the tray table. If the seat is hard and nonporous or leather or pleather, you can wipe that down, too. (Using wipes on upholstered seats could lead to a wet seat and spreading of germs rather than killing them.)

-

What should I do if I feel sick?

If you’ve been exposed to the coronavirus or think you have, and have a fever or symptoms like a cough or difficulty breathing, call a doctor. They should give you advice on whether you should be tested, how to get tested, and how to seek medical treatment without potentially infecting or exposing others.

-

“It’s mainly a timing issue,” Dr. Bhattacharya said. “If you have circulating cells and molecules, they’ll eventually find the infection. But you’d rather have a more immediate response.”

Without a strong mucosal response, injected vaccines may be less likely to produce so-called sterilizing immunity, a phenomenon in which a pathogen is purged from the body before it’s able to infect cells, Dr. Durbin said. Vaccinated people might be protected from severe disease, but could still be infected, experience mild symptoms and occasionally pass small quantities of the germ onto others.

Reliably rousing mucosal immunity isn’t easy, however — and vaccines that specifically target them come with their own drawbacks. Although FluMist, a nasal spray vaccine containing weakened flu viruses, has been shown to be more effective than flu shots in young children, its performance is more lackluster in adults. And the oral polio vaccine has been linked to a very small number of cases of polio after the weakened virus in the product mutated.

Designing a mucosal vaccine with less risky ingredients, such as inactivated viruses or genetic material, could circumvent that issue. But these more innocuous formulations could be too weak to stimulate a long-lasting immune response.

“You want the vaccine to be strong enough to get in and do what it needs to do, but it can’t cause a lot of symptoms,” Dr. Durbin said. “It’s a really difficult balance.”

Much of mucosal immunity also remains mysterious to researchers. “A lot of what we know about the rest of the immune system kind of goes out the window when we’re talking about a mucosal site,” said Dr. Frances Eun-Hyung Lee, a physician and immunologist at the Emory Vaccine Center. There are also fewer tried-and-true technologies for developing nasal and oral vaccines, compared with injectables.

All these factors can introduce speed bumps in the vaccine-development timeline, as researchers work to ensure both safety and effectiveness, Dr. August said. That means mucosal recipes might not be among the first generation of coronavirus vaccines. But perhaps that’s all the more reason to invest in them earlier, he said.

[Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.]