Inflation is upon us. Growth expectations are falling. Markets are worried about Federal Reserve interest rate hikes.

Depending on your vintage, you have probably seen this a few times before. It happens once a decade or so when the economy starts running overly hot, economists tug their chins with concern about inflation. Eventually the Fed hikes and we get a recession. Then we all tug our chins about what to do about the recession.

But this time feels different. Typically, when the business cycle runs hot there is no shortage of inflationistas who come bearing gifts. Some sell gold; others warn of the Fed’s control over the money supply. Late cycle is when the inflationista thrives–often engaging in hyperbole about the actual dangers.

What we do not typically see late cycle, however, are shortages, travel disruptions and general economic chaos. But that is precisely what we are seeing today. That is why you can hear, if you listen carefully, cautious whispers in the financial press and in central banks about “stagflation.”

Stagflation is a different beast from normal inflation. Normal inflation can be cured by a short-term shock to the system in the form of the Fed hiking interest rates. But stagflation does not respond to the standard medicine. It hangs around like a bad smell even after the economy enters recession and unemployment climbs. We last saw these dynamics in the 1970s—and they were punishing.

Normal inflation and stagflation have different causes. A standard inflation arises because there is too much spending in the economy at any given time. Too much money chasing too few goods, as the old adage has it. Remove the spending—as happens when the Fed generates a recession—and the inflation goes away.

Stagflation, on the other hand, occurs because of bottlenecks in the markets for labor and goods. That is, something gets “stuck” in these markets. The smooth functioning of the economic machine—in which the baker bakes your bread, the truck driver delivers it to the store and a driver brings it to your doorstep—breaks down.

In the 1970s this arose due to two forces. The first was oil shortages. Arab countries sought to punish the United States for backing Israel in the Yom Kippur War and restricted the oil supply. Gas stations soon filled up, not with fuel, but with queues of angry motorists with empty tanks.

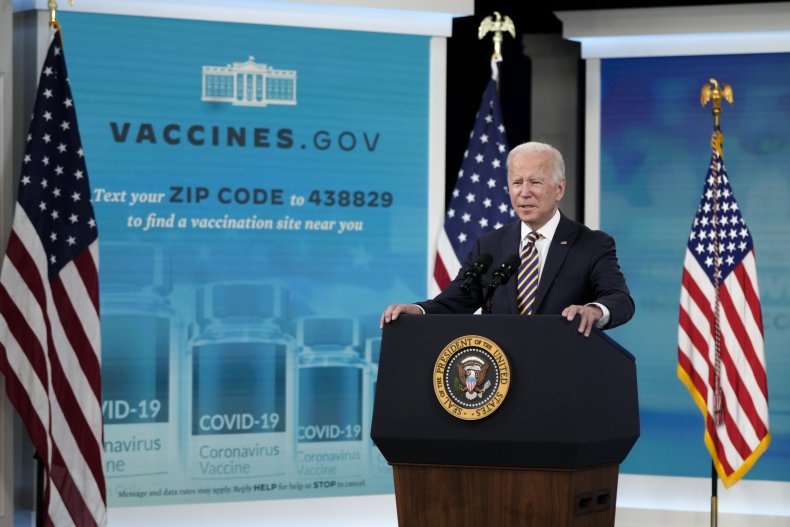

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

The second force was labor shortages. These were caused by labor unions that had gained a huge amount of confidence from the waves of radicalism in the 1960s. The unions pushed for strikes hard. The strikes removed workers from the economy. Factories shut down and prices spiraled. The striking workers then complained about their wages being too low relative to rising prices, engaged in more strike action and bid up wages—which forced employers to raise prices still further. This toxic dynamic is known as a “wage-price spiral.”

Today we appear to be seeing similar dynamics. But instead of a Middle Eastern war, we have chaotic shipping delays caused by heavy-handed laws put in place around the world in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Domestically, workers have been scared out of their wits. Some are scared that if they go to work, they might catch the virus. Others are scared that if they take a vaccine their company is forcing them to take, they will experience dangerous side effects. So, they quit or get fired. Or they look for a different job. Or they call in sick.

The result is labor shortages. And as the supply of labor shrinks, its price—that is, wages—rises. Prices rise with wages—and workers, holding all the cards because of the tight labor market, demand more wage rises. We arrive at the same dynamics we saw in the 1970s, but via a different mechanism.

Once you understand it in this way, everything falls into place. The 38,000 care workers laid off in September and the flight disruptions, for example? Vaccine mandates creating chaos in the markets for health care and transport services. Indeed, if you look carefully at the state-by-state jobs data you can see that states with vaccine mandates have far more layoffs than states that have banned vaccine mandates.

Stagflation caused by massive interventions in the economy may not respond to standard economic medicine. This is not to say that the huge $3.5 trillion spending bill will not make things worse—it obviously will. But simply cancelling the bill will not stop the disruptions caused by lockdowns and vaccine mandates.

The same is true of Fed policy. Hiking interest rates and shaking the economy up may nip inflation in the bud. But it may not. It may just create a recession and mass joblessness as inflation continues to march forward—as happened in the 1970s.

The only surefire cure is to stop the interventions—the lockdowns and the mandates. Over the past two years, politicians have become far too eager to intervene in the economy in the name of public health. Economists have been strangely silent about the effects these interventions would have on the economy—many swam with the tide.

We are now starting to see the effects of these interventions. Sadly, we cannot undo what has been done, and it seems we will have to live with a lot of economic discomfort for some time. But moving forward, it is imperative that we be honest about the underlying causes of the discomfort, and clear-minded about the proper solutions—no matter how much more fashionable it is to play armchair epidemiologist.

Philip Pilkington is a macroeconomist with nearly a decade of experience working in investment markets, he is the author of the book The Reformation in Economics: A Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Economic Theory.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.