Oral arguments in a case challenging the separation of church and state may have pulled the curtain back on the politicization of the Supreme Court and how its new conservative majority may impact future rulings.

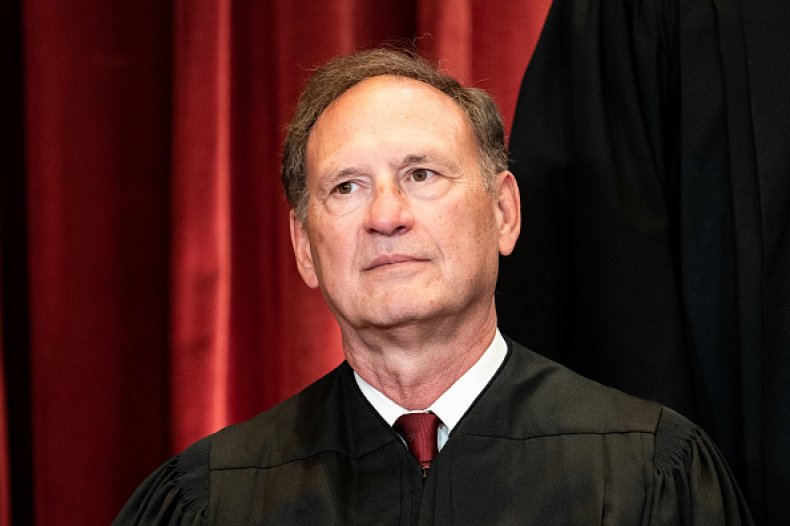

During Wednesday’s hearing on Carson v. Makin—a case asking the justices to decide whether the exclusion of religious schools from Maine’s public funding program violates religious freedoms—Justice Samuel Alito, one of the bench’s six conservatives, asked Maine’s Chief Deputy Attorney General Christopher Taub if schools teaching critical race theory would also be excluded from the state’s tuition-assistance program.

“I don’t really know exactly what it means to teach critical race theory, so I think the Maine legislature would have to look at what that means,” Taub responded. “But I will say this: That if teaching critical race theory is antithetical to a public education, then the legislature would likely address that.”

In his arguments, Taub emphasized that the program was built to follow Maine’s goals to promote “religious neutrality” in public education, adding that schools that hypothetically taught Marxism or white supremacy would also be disqualified.

Alito’s question comes as the public’s opinion of the Supreme Court has continued to decline.

A Quinnipiac poll released last month found that more than 6 in 10 Americans think the high court is motivated by politics rather than the law—a six-point increase from two years ago.

Many have expected the justices to rule against Maine in Carson due to the court’s expanding interpretation of the free exercise and clause and its increasing willingness to allow states to channel funds to sectarian institutions.

“At the same time as the Court has been expanding the meaning of the free exercise clause, the court has been limiting the scope of the establishment clause,” University of Maine School of Law’s Dmitry Bam told Newsweek. “It has been clear that when private parties choose to use public funds for religious uses, that does not raise an establishment clause concern.”

Erin Schaff/Getty

In Maine, some school districts lack secondary schools. In order to ensure that kids across the state have access to K-12 education, Maine provides money to students who need to attend schools outside their districts. However, in order for a student to qualify for the subsidy, they must prove the chosen school is “nonsectarian.”

In Carson, two sets of parents—whose children are eligible to receive state assistance and who want to send their children to Christian schools—are suing the state for excluding the institutions from funding for providing religious instruction.

Citing the Supreme Court’s decision in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue last year, the parents argue that Maine is infringing on their constitutional right to religion under the First Amendment.

In Espinoza, another school-funding case, the justices ruled that while states are not required to offer money for private education, they cannot exclude families or schools form accessing those funds because of a school’s religious status.

In Carson, a lower court ruled in favor of the state, deciding that Espinoza only prohibited exclusion based on religious status and not use.

Thus, if schools are being excluded based on their religious affiliation, those assistance programs would be unconstitutional.

But if those schools are being excluded for using religion in its educational instruction, the lower court said Maine can deny public funding under the Constitution’s non-establishment clause, otherwise known as the separation of church and state.

Daniel Slim/AFP

The state has also pointed out that religious schools may not accept public funds because doing so would change how these institutions operate.

For example, the two schools in question—Temple Academy and Bangor Christian School—refuse to hire gay teachers.

But, as the state points out, it would be unlawful for the schools to discriminate based on sexual orientation under the Maine Human Rights Act. The schools are currently able to refuse gay teachers under an exception provided to religious organizations “that do not receive public funds” in the state.

On Wednesday, both Justices Clarence Thomas and Elena Kagan questioned whether the case had any standing, pointing out that neither of the schools have indicated that they will accept state subsidies.

When asked by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, if the parents would be open to sending their child to another religious school if Temple Academy did not accept state funding, attorney Michael Bindis, who is representing the parents, said they would as long as the education aligned with their religious beliefs.

Maine is arguing that the goal of its program is to offer uniformity in K-12 education, and because the state has concluded that public education “should be a nonsectarian one,” only students attending nonsectarian schools should be eligible for tuition assistance.

So while one set of the parents argue that they would be unable to send their child to a Christian school without funding, Maine is countering that the state has no obligation to provide funds to a sectarian education.

Rather, the state says the benefit being offered is solely “a free public education”—like other parents in Maine who have secondary schools in their district, the plaintiffs can either send a child to one of Maine’s public schools or pay for religious training.

On Wednesday, Bindis argued, “This is not subsidizing the exercise of a right. It is conditioning the availability of an otherwise available public benefit on the surrender of a constitutional right.”

“The government cannot compel a citizen to choose between [the] exercise of a right protected by the First Amendment and participation in an otherwise available public program,” he added.