Frustration over pandemic reopening plans is growing in New Jersey’s affluent suburbs, where taxes are high and many students are barely in classrooms.

SOUTH ORANGE, N.J. — Kate Walker, a New Jersey mother of three, says she feels like one of the lucky ones: She enrolled her children in a Catholic school for September before a wait-list started.

But she has held off making a final tuition deposit, hoping that her town’s public school district, South Orange-Maplewood, brokers a lasting solution with the teachers’ union, which had resisted a planned phased-in return to school, citing coronavirus safety concerns.

“I’ve lost a lot of faith in the district,” said Ms. Walker, who participated in a recent sit-in outside her 7-year-old son’s elementary school. “We’ve been stopped and started a dozen times.”

Most districts in New Jersey have partially reopened, but one in four children still live in a district where public schools are closed. No state in the Northeast had more districts relying on all-virtual teaching in early March than New Jersey, according to Return To Learn, a database created by a conservative think tank, American Enterprise Institute, and Davidson College. Nationwide, only seven states had a greater proportion of all-remote instruction.

As the distribution of Covid-19 vaccines has accelerated and President Biden has signaled a push for broader reopenings, frustration among parents has grown, particularly in New Jersey’s affluent suburbs, where schools with stellar reputations are a key reason families are willing to pay some of the nation’s highest taxes.

These parents have filed federal lawsuits, held protests, created online petitions and stormed virtual board of education meetings to demand expanded in-person instruction.

The pressure to open schools more fully comes as the infection rate in New Jersey, which is small and densely populated, remains stubbornly high: With a weekly average of 45 cases for every 100,000 residents, the state leads the nation in new infections, according to a New York Times database.

In Princeton, where schools are among the best in the state, hundreds of middle and high school parents have joined webinars and school board meetings, many asking for additional face-to-face teaching. In Closter, in northern Bergen County, an online petition urging an immediate return to five days of school, gathered hundreds of signatures within hours.

The drumbeat intensified after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced a major policy shift on Friday, reducing its distancing recommendations to three feet from six feet for all elementary schools and for middle and high schools in areas where the virus infection rate is not high.

Anger at the pace of reopening has led some families who can afford it to enroll their children in private schools, start home-schooling them or move.

New Jersey’s school districts expect to have an estimated 26,000 fewer students by fall, according to state aid funding records. Experts have warned that an exodus of wealthier families could further weaken public schools at a critical moment: while confronting student learning loss.

In South Orange-Maplewood, enrollment in October had dipped by 327 students. By the next school year, officials estimate it could drop by another 62 students, resulting in a total decline of about 5 percent.

“We believe most of it is from people deciding to either move their students into private schools or to keep them home for home-schooling,” Paul Roth, the district’s business administrator, said at a recent board of education meeting.

After lawsuits and the intervention of a mediator, some of the district’s youngest children restarted school in person on March 15, but most students have not been back in class since the start of the pandemic.

If enough children leave a district in New Jersey, it could lead to cuts in state aid, scaled-back programming or potentially layoffs. In South Orange-Maplewood, however, the decline in enrollment was not expected to cause a reduction in state funding, a spokeswoman said.

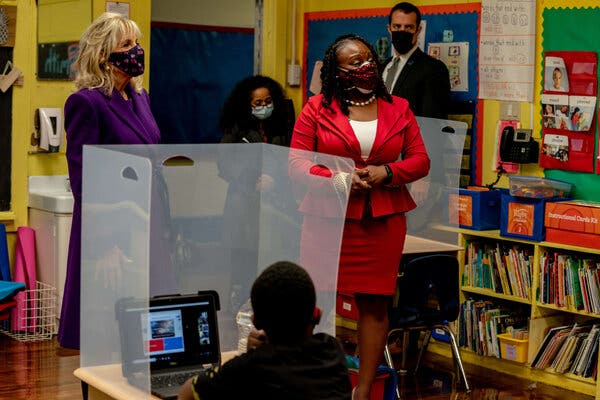

The first lady, Jill Biden, traveled to New Jersey last week to promote the $1.9 trillion stimulus package, which includes $130 billion for schools. Dr. Biden’s visit drew attention to the state’s reputation for exceptional schools, which were ranked No. 1 in the country this school year by Education Week and U.S. News & World Report.

Several New Jersey cities and counties have held educator-only vaccine distribution events. But the virus’s hold on the state has left teachers and their powerful unions wary of expanded reopening.

Two days after Dr. Biden’s visit, Gov. Philip D. Murphy offered his most unambiguous comments yet about school reopenings, suggesting a shift away from the largely hands-off approach he had maintained since September. He noted that relatively few cases of the virus in New Jersey — 890 out of more than 850,000 total cases — had been linked to in-school transmission.

“It is time to stem this tide before more students fall away,” Mr. Murphy said. “A full year out of their classrooms is not how students move forward or how our world-class extraordinary educators move forward in their professions, for that matter.”

Public schools in the state’s largest cities remain closed, though many are preparing to reopen to some students in mid-April.

“It is our complete expectation that every school will be open, and every student and educator will be safely in their classrooms for full-time, in-person instruction for the 2021-2022 academic year,” Mr. Murphy said.

Marie Blistan, a close ally of Mr. Murphy who leads the New Jersey Education Association, the state’s largest teachers’ union, said expanded vaccination access for educators and the infusion of federal funding had put schools in a better position to reopen more fully.

“I agree with the governor that it’s time for everybody to get back to normal, but to do it safely,” she said, adding that she understood parents’ frustration.

“They’re upset and angry and I absolutely feel for them,” she said. “But in the end our members have advocated for the health and safety of their kids.”

Parent frustration is particularly acute in towns where private schools have been open all year.

Meg Asaro, a mother of two, sold her house in Montclair in December and moved to Pennington, about 60 miles south, after watching her first-grader, Bryce, struggle with all-virtual classes. Some of Montclair’s public schools, which have been closed since last March, are making plans to reopen next month, but in Pennington, Bryce attends a public school five days a week.

Frequently Asked Questions About the New Stimulus Package

The stimulus payments would be $1,400 for most recipients. Those who are eligible would also receive an identical payment for each of their children. To qualify for the full $1,400, a single person would need an adjusted gross income of $75,000 or below. For heads of household, adjusted gross income would need to be $112,500 or below, and for married couples filing jointly that number would need to be $150,000 or below. To be eligible for a payment, a person must have a Social Security number. Read more.

Buying insurance through the government program known as COBRA would temporarily become a lot cheaper. COBRA, for the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, generally lets someone who loses a job buy coverage via the former employer. But it’s expensive: Under normal circumstances, a person may have to pay at least 102 percent of the cost of the premium. Under the relief bill, the government would pay the entire COBRA premium from April 1 through Sept. 30. A person who qualified for new, employer-based health insurance someplace else before Sept. 30 would lose eligibility for the no-cost coverage. And someone who left a job voluntarily would not be eligible, either. Read more

This credit, which helps working families offset the cost of care for children under 13 and other dependents, would be significantly expanded for a single year. More people would be eligible, and many recipients would get a bigger break. The bill would also make the credit fully refundable, which means you could collect the money as a refund even if your tax bill was zero. “That will be helpful to people at the lower end” of the income scale, said Mark Luscombe, principal federal tax analyst at Wolters Kluwer Tax & Accounting. Read more.

There would be a big one for people who already have debt. You wouldn’t have to pay income taxes on forgiven debt if you qualify for loan forgiveness or cancellation — for example, if you’ve been in an income-driven repayment plan for the requisite number of years, if your school defrauded you or if Congress or the president wipes away $10,000 of debt for large numbers of people. This would be the case for debt forgiven between Jan. 1, 2021, and the end of 2025. Read more.

The bill would provide billions of dollars in rental and utility assistance to people who are struggling and in danger of being evicted from their homes. About $27 billion would go toward emergency rental assistance. The vast majority of it would replenish the so-called Coronavirus Relief Fund, created by the CARES Act and distributed through state, local and tribal governments, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. That’s on top of the $25 billion in assistance provided by the relief package passed in December. To receive financial assistance — which could be used for rent, utilities and other housing expenses — households would have to meet several conditions. Household income could not exceed 80 percent of the area median income, at least one household member must be at risk of homelessness or housing instability, and individuals would have to qualify for unemployment benefits or have experienced financial hardship (directly or indirectly) because of the pandemic. Assistance could be provided for up to 18 months, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Lower-income families that have been unemployed for three months or more would be given priority for assistance. Read more.

Ms. Asaro said a desire for in-person education was largely responsible for her family’s decision to leave.

Bryce now boards a school bus each morning at 7:07. “He is like a completely different child here,” Ms. Asaro, 53, said.

Private schools and the state’s broad network of Catholic schools, some of which were struggling for survival as enrollment declined over decades, appear to be benefiting from decisions made by public school districts.

“We had an influx of students from the public sector wanting to come into our schools quite simply because we were open,” said Vincent de Paul Schmidt, the superintendent of schools in the Diocese of Trenton, which operates 42 schools. A spokeswoman for the Archdiocese of Newark said its 74 schools had seen a similar uptick in admissions.

St. Gregory the Great Academy, a Catholic elementary school in Hamilton, N.J., near Trenton, has a waiting list for the first time since 2007. The principal, Jason C. Briggs, said 45 new students had registered next year for the school, which charges $5,775 in tuition.

“The interest in enrollment is shocking, to be honest,” Dr. Briggs said. “I have not even placed an ad.”

South Orange-Maplewood, a district of about 7,000 students, has had one of the most convoluted reopening rollouts in the state.

Last week, a judge overseeing a lawsuit the district brought against its teachers union, said sixth- and ninth-grade teachers should report to school later this month, joining the kindergarten through second-grade educators who had already returned.

The district, in a statement, called it “an important and critical step in the right direction.”

Representatives from the union, which has cited building conditions for employees’ reluctance to teach inside schools, did not respond to requests for comment.

“This has never been about a challenge to the district,” the union’s president, Rocio Lopez, said in a statement after the judge’s ruling. “This was about having our concerns and ideas heard, respected and able to put into action so that schools could open safely.”

Gina Patterson moved nine years ago to Maplewood, a commuter town about 25 miles from Midtown Manhattan. Her 9-year-old daughter, Lily, had not been in class in nearly a year when Ms. Patterson said she reached a breaking point in February.

Concerned about academic rigor and limited socialization, she enrolled Lily in a nearby private school, Far Brook School, where tuition is $40,000 a year.

“It was emotionally a very hard decision to make,” Ms. Patterson said. “We moved here to participate in the public school system.”

But she said her trust in the district had eroded.

“The kids were really left out of this conversation,” she said, “and that’s been really eye-opening.”