The White House is setting benchmarks, such as a 4 percent unemployment rate, to mark a full recovery. But the wild card remains the same: the virus itself.

WASHINGTON — The Biden administration, with hundreds of billions of dollars to spend to end the Covid crisis, has set a series of aggressive benchmarks to determine whether the economy has fully recovered, including returning to historically low unemployment and helping more than one million Black and Hispanic women return to work within a year.

But restoring economic activity, which was central to President Biden’s pitch for his $1.9 trillion stimulus package, faces logistical and epidemiological challenges unlike any previous recovery. Infectious new variants of the virus are spreading. Strained supply chains are holding up the distribution of rapid Covid-19 tests, which could be critical to safely reopening schools, workplaces, restaurants, theaters and concert venues.

Then there are questions of whether the money can reach schools and child care providers quickly enough to make a difference for parents who were forced to quit their jobs to care for their children.

The money from the rescue plan “will absolutely allow us to pull forward that end date,” said Charlie Anderson, the director of economic policy and budget for the White House’s coronavirus response team. “It’s very hard to tell how much, but I can tell you it will absolutely supercharge what we’re doing.”

Privately, Mr. Biden’s aides are tracking health and economic data — like the capacity levels of day care centers — to gauge their success. They are also setting broad targets, like a return to a 4 percent unemployment rate, which would be just above the nation’s prepandemic rate, by next year.

Similar promises came back to bite Mr. Biden in 2009, as vice president, when he oversaw a considerably smaller economic stimulus package signed by President Barack Obama to lift the country from the Great Recession. Shortly before he and Mr. Obama took office that January, their advisers predicted the measure would keep unemployment from rising above 8 percent — a projection that haunted the administration as the economy slogged on for years.

This recovery is showing more favorable signs for the Biden administration. Economic optimism is rising as the pace of vaccinations steadily increases. Unemployment has already fallen from its pandemic peak of 14.8 percent last April to 6.2 percent in February. Federal Reserve officials now expect the unemployment rate to slip below 4 percent by next year and for the economy to grow faster this year than in any year since the Reagan administration, thanks in part to Mr. Biden’s rescue package.

The Federal Reserve chair, Jerome H. Powell, told reporters last week that federal spending to combat the crisis was “going to wind up very much accelerating the return to full employment.”

He added, “It’s going to make a huge difference in people’s lives, and it has already.”

But risks remain. For the economy to fully bounce back, Americans need to feel confident in returning to shopping, traveling, entertainment and work. No matter how much cash the administration pumps into the economy, recovery could be stalled by the emergence of new variants, the reluctance of some Americans to get vaccinated and, in the coming weeks, spotty compliance with social distancing guidelines and other public health measures before a critical mass of Americans is inoculated.

“We’re being really cautious about our expectations about the speed” of the economic rebound, said Heather Boushey, a member of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers. “Part of this is establishing trust with the American people that we contain the virus, and that it’s safe, and then the economic activity will come up.”

Americans will also have to be willing to change their habits. As new infections have declined, so too has coronavirus testing. But public health experts say more testing — not less — will be critical for the economy to recover. When Mr. Biden ran for office, and again after he was sworn in, he promised to create a “pandemic testing board,” akin to the wartime production board that President Franklin D. Roosevelt created to help bring the country out of the Great Depression. Mr. Biden described the approach as a “full-scale wartime effort.”

His coronavirus testing coordinator, Carole Johnson, said the board, composed of officials from across government agencies, had been meeting to discuss how to work with the private sector to expand testing capacity, and to lay out plans to spend tens of billions of dollars from the stimulus bill for testing and other mitigation measures.

“We know that we’re going to continue to need to grow as we go forward,” she said of the nation’s testing capacity.

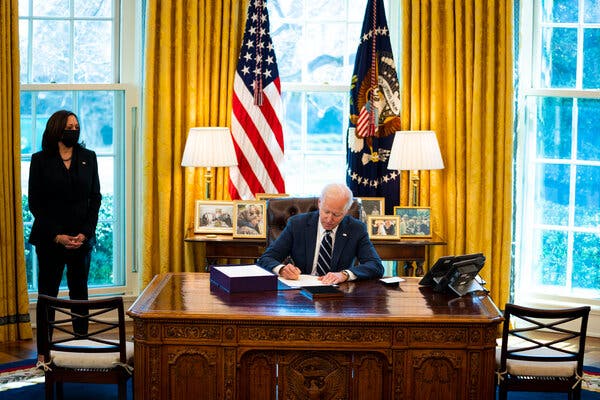

Mr. Biden made grand promises in pushing his American Rescue Plan to swift passage in Congress this month.

“This is what this moment comes down to,” he said in February. “Are we going to pass a big enough package to vaccinate people, to get people back to work, to alleviate the suffering in this country this year? That’s what I want to do.”

Mr. Biden got virtually everything he wanted. Now administration officials must make good on his vow.

The legislation he signed centers on $1,400 direct payments to low- and middle-income Americans, expanded unemployment benefits, aid to renters facing eviction and a variety of programs to help the poor. The president and his aides have said that spending is intended to help the most vulnerable people in the country stay in their homes and keep food on the table.

But Congress will not continue borrowing trillions of dollars to tide citizens over indefinitely. The economy will not fully rebound from the recession brought on by the virus until the pandemic is over.

To that end, hundreds of billions of dollars in the bill are earmarked to speed vaccinations, bolster testing, help businesses return to full capacity sooner and ease the return to work for Americans — disproportionately women of color — who were forced to leave their jobs to care for young children.

Frequently Asked Questions About the New Stimulus Package

The stimulus payments would be $1,400 for most recipients. Those who are eligible would also receive an identical payment for each of their children. To qualify for the full $1,400, a single person would need an adjusted gross income of $75,000 or below. For heads of household, adjusted gross income would need to be $112,500 or below, and for married couples filing jointly that number would need to be $150,000 or below. To be eligible for a payment, a person must have a Social Security number. Read more.

Buying insurance through the government program known as COBRA would temporarily become a lot cheaper. COBRA, for the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, generally lets someone who loses a job buy coverage via the former employer. But it’s expensive: Under normal circumstances, a person may have to pay at least 102 percent of the cost of the premium. Under the relief bill, the government would pay the entire COBRA premium from April 1 through Sept. 30. A person who qualified for new, employer-based health insurance someplace else before Sept. 30 would lose eligibility for the no-cost coverage. And someone who left a job voluntarily would not be eligible, either. Read more

This credit, which helps working families offset the cost of care for children under 13 and other dependents, would be significantly expanded for a single year. More people would be eligible, and many recipients would get a bigger break. The bill would also make the credit fully refundable, which means you could collect the money as a refund even if your tax bill was zero. “That will be helpful to people at the lower end” of the income scale, said Mark Luscombe, principal federal tax analyst at Wolters Kluwer Tax & Accounting. Read more.

There would be a big one for people who already have debt. You wouldn’t have to pay income taxes on forgiven debt if you qualify for loan forgiveness or cancellation — for example, if you’ve been in an income-driven repayment plan for the requisite number of years, if your school defrauded you or if Congress or the president wipes away $10,000 of debt for large numbers of people. This would be the case for debt forgiven between Jan. 1, 2021, and the end of 2025. Read more.

The bill would provide billions of dollars in rental and utility assistance to people who are struggling and in danger of being evicted from their homes. About $27 billion would go toward emergency rental assistance. The vast majority of it would replenish the so-called Coronavirus Relief Fund, created by the CARES Act and distributed through state, local and tribal governments, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. That’s on top of the $25 billion in assistance provided by the relief package passed in December. To receive financial assistance — which could be used for rent, utilities and other housing expenses — households would have to meet several conditions. Household income could not exceed 80 percent of the area median income, at least one household member must be at risk of homelessness or housing instability, and individuals would have to qualify for unemployment benefits or have experienced financial hardship (directly or indirectly) because of the pandemic. Assistance could be provided for up to 18 months, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Lower-income families that have been unemployed for three months or more would be given priority for assistance. Read more.

Those provisions include nearly $30 billion for to ramp up vaccine deployment, support struggling community health centers and hire 100,000 public health workers. It also has nearly $50 billion for more Covid-19 testing, $122 billion for schools and both direct spending and expanded tax credits meant to increase the availability of child care.

In keeping with Mr. Biden’s focus on racial equity across a wide range of policy endeavors, administration officials say they will look at how quickly women of color rejoin the labor force to gauge how well equity efforts are working.

None of that spending is guaranteed to immediately change the course of the crisis. Schools, for example, are not required by the legislation to spend their additional dollars to reopen sooner, though administration officials are confident the money will help more students return to in-person learning in the coming months.

Sometime next month, vaccine distribution will enter a new phase. The supply of doses will exceed the number of people looking for shots and public officials are likely to focus more on convincing reluctant Americans to agree to be vaccinated.

Perhaps no spending effort will challenge the administration as much as increased testing.

Right now, testing is largely used as a diagnostic tool to detect whether someone is infected. Moving forward, testing is expected to function more as a screening tool that helps Americans feel more comfortable returning to normalcy.

The rescue plan includes nearly $48 billion for the administration to expand testing, contact tracing and other measures to track and contain the spread of the virus.

The administration has not said how it will spend all of that money, though the Department of Health and Human Services announced on Thursday that it would invest $10 billion in coronavirus screening for schools, with the goal of returning to in-person learning by the end of the school year. An additional $2.25 billion will go toward coronavirus testing in underserved communities.

“We’re going to need widespread testing for this virus probably for the next several years,” said Dr. Ashish K. Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health. “Right now, it’s all about just management of disease. But over time, as the pandemic gets under control, there are a whole series of things we want to do where testing will add a layer of confidence — everything from getting on an airplane to going into a restaurant to going to a concert.”

But there are obstacles to that plan, including a shortage of the kind of rapid tests that are necessary to screen a large population. Michael Mina, an immunologist and epidemiologist at Harvard University, said onerous Food and Drug Administration regulations were delaying the approval of new rapid antigen tests that could fill that gap.

“I feel very firmly that the Biden administration is hampered by a regulatory framework that is not in a position to actually tackle this pandemic, that is holding up the tools that are required to effectively curb transmission, to keep schools and businesses safe,” he said.

Mr. Biden, who criticized his predecessor President Donald J. Trump for interfering with the work of the F.D.A., is hardly in a position to intervene in a regulatory matter. But his coronavirus testing coordinator, Ms. Johnson, said in an interview that the administration was closely tracking the supply chains for tests to determine what it could do to ensure widespread testing at schools become a reality.

“We make policy decisions informed by where the supply is,” she said.

Administration officials are also closely tracking the C.D.C.’s infection data to guide their spending decisions and determine how to measure success. The uncertainty in the models based on that data, they say, underscores the challenge ahead of them: Four weeks from now, the nation could have as many as 511,000 new weekly cases — or as few as 138,000.