For three and a half years of Donald Trump’s presidency, Democrats have repeated a phrase as a reminder, talisman and battle cry: “This is not normal.”

Monday night, they gathered virtually to nominate a challenger, Joseph R. Biden. And boy, was it ever not normal — in ways that even Mr. Trump’s direst critics in 2016 could not have predicted.

The first night of the Democratic National Convention, exiled by coronavirus to the ether of teleconferencing and prerecording, was an experiment in how to sound the theme “We the People” with a “we” constructed entirely virtually.

At its shakiest, it was, like much pandemic-era TV, uncanny, disjointed and unsettlingly weird. (To its credit, though, there were few of the glitches that have riddled so much bandwidth-dependent live television.) At its most engaging, it dispensed with some relics of televised conventions and found faster-paced and more intimate alternatives.

On cable news, there were no pundit panels jawboning all day on location. There was no location, really — most of the convention took place in a Milwaukee of the mind. (Sadly, without virtual fried cheese curds.) There were no floor interviews with delegates for also-ran candidates. No placards. No funny hats. And above all, no cheering, hooting crowds.

Instead, the teleconvention kept a few standards (like the Bruce Springsteen–soundtracked montage) and borrowed from a grab bag of other TV formats, from talk show to cable news to reality-TV reunion special. And it was all hosted for the night by the actress Eva Longoria from the floor of a cable-news-like studio, a kind of ersatz DNCNN. “We had hoped to gather in one place,” she said early on.

The very reason they couldn’t was linked to a key political theme of the night: the Covid-19 pandemic, and the Trump administration’s handling of it. This meant that, more than usual, the medium was the message.

The program’s very existence was a kind of political argument: If this doesn’t look normal, it’s because none of this is normal right now. President Trump, the presentation said visually, had broken normality; the Democrats, with an assortment of appeals both to Republicans and to their own party’s left, promised to restore it.

Some viewers on social media said the show looked like a telethon, and it often did, from the stories of hardship to the heart-tugging sea-to-shining-sea musical numbers. (These included Leon Bridges on a rooftop and Maggie Rogers on a Maine shore.)

But why do you hold a telethon? For disasters and diseases. For emergencies.

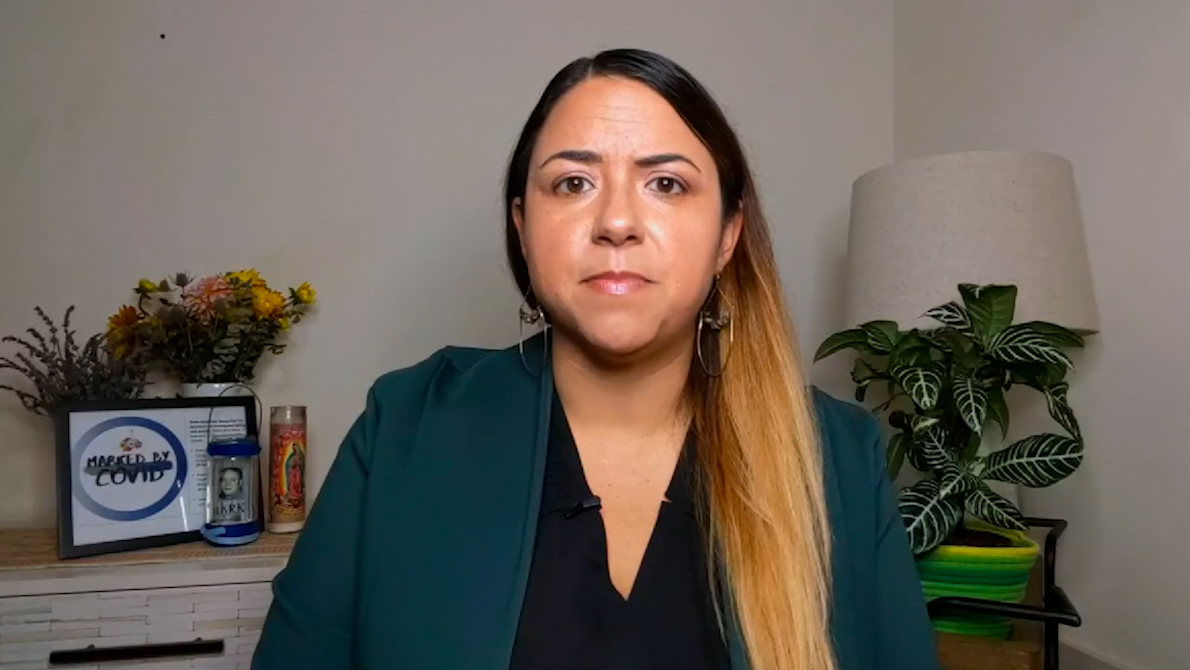

Some of the most memorable moments in the first hour leaned into this feeling of crisis, like Ms. Longoria’s interviews with Americans affected by the pandemic and economic crash. A testimonial from Kristin Urquiza, whose father voted for Mr. Trump and died of coronavirus, was especially searing. “His only pre-existing condition,” she said, “was trusting Donald Trump.”

Back

transcript

‘He Paid With His Life,’ Daughter of Trump Supporter Says

Kristin Urquiza, whose father died of the coronavirus, spoke before the Democratic National Convention about his misplaced faith in President Trump.

-

My dad, Mark Anthony Urquiza, should be here today. But he isn’t. He had faith in Donald Trump. He voted for him, listened to him, believed him and his mouthpieces when they said that coronavirus was under control and going to disappear. My dad was a healthy 65-year-old. His only pre-existing condition was trusting Donald Trump — and for that he paid with his life. I am not alone. Once I told my story, a lot of people reached out to me to share theirs. They asked me to help them keep their communities safe, especially communities of color, which have been disproportionately affected.

A virtual chorus sang the national anthem in red, white and blue T-shirts. The program quickly rotated in Democratic stars of the resistance and pandemic eras — Gov. Andrew Cuomo of New York and his PowerPoint charts, a string of Mr. Biden’s primary challengers and their dueling bookcases.

Their testimonials for the nominee framed the election as a choice between his experience and caring (a case of aspirin to anyone who had “empathy” in their drinking game) and Mr. Trump’s chaos and rage. Mr. Biden appeared himself, unusually for a nominee on the first night of a convention, hosting a round table on race and policing, his guests arrayed on a semicircle of screens.

The program also adapted to more recent news, including numerous calls to defend the post office, plagued by delays (which many charged are meant to help Mr. Trump by undermining mail-in voting). If the “Lock her up” Republicans of 2016 were the party of jail, Monday night’s Democrats were the party of mail.

There were a lot of ideas smashed against each other abruptly, and not all of them genius. Having the Republican former governor of Ohio, John Kasich, speak about America at a “crossroads” while standing at a literal crossroads was perhaps not the stunning visual someone imagined. (Also, it looked more like a slight left turn, I assume not a reference to Mr. Biden’s politics.) And several straight-to-camera speeches felt deflated by the lack of a crowd, like a State of the Union response.

How much viewers saw depended on their platform of choice. The production was even more prepackaged than a typical convention, and the broadcast networks, which joined for the last hour, cut away often for commentary, while CNN and MSNBC carried more of the DNC feed. (During Sean Hannity’s show, Fox News put much of the proceedings in a postage-stamp window.)

As much changed since 2016, a couple things notably stayed the same. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and the former first lady Michelle Obama were the star Monday-night speakers then and now.

In 2016 Mr. Sanders, addressing a raging crowd filled with his discontented progressive supporters after a bitter primary, was half rock star and half lion tamer. This year, speaking remotely in front of a Green Mountains forest worth of stacked firewood, he was more of an earnest testimonial giver, congratulating his followers for moving the party their way while attacking the incumbent for his nominee: “Nero fiddled while Rome burned. Trump golfs.”

Ms. Obama, the headliner, famously gave her 2016 audience the upbeat message, “When they go low, we go high.” This time, she went hard.

But she did it by speaking softly (and wearing a “VOTE” necklace). Ms. Obama’s message, intense and informed by the four years that passed, hit harder because it was delivered to fit the no-audience format. Instead of building to cheering and catharsis, she confided and emoted, even joked, with the control of a veteran talk-show host. She was framed in an intimate close-up and spoke in an urgent hush that asked the viewer to lean in.

She attacked, much more than in the past; assessing Mr. Trump’s fitness she said, “It is what it is,” a cutting reference to his response in a TV interview to the pandemic death toll. But she did it in the voice not of an office holder but of a best-selling author, familiar TV friend and popular personality among nonpolitical junkies. “You know I hate politics,” she said, and as much as possible from a veteran convention speaker, it was convincing.

For the more partisan in the audience, Mr. Sanders delivered another message: “This is not normal, and we must never treat it like it is.” Watching this experiment in dystopian electioneering, there was little chance of that.