For over two weeks, Danielle Gilliam has lived at her job.

Inside Swan House in Worcester, one of the Seven Hills Foundation’s 100-plus group homes for people with developmental disabilities in Massachusetts, Gilliam has slept in shifts with her two co-workers.

They keep up a steady routine of meals and bedtimes for the five adults who reside there. They arrange FaceTime calls to loved ones, now kept at distance away in their own homes. They fend off the moments when the bouts of restlessness and stir craziness rush in since they started their around-the-clock work life on April 6.

In her 15 years in the field, Gilliam, 44, the house’s residence director, has never had an experience like this before. And while group home caretakers like her are finding new hurdles to their daily work in the age of COVID-19, Gilliam says there are plenty of ways to spend the day cooped up inside, from movie nights to staff-performed musicals.

“If you can think of it, we’re doing it,” she says.

The days are long, but Gilliam knows the alternative — if the house didn’t go into lockdown when it did.

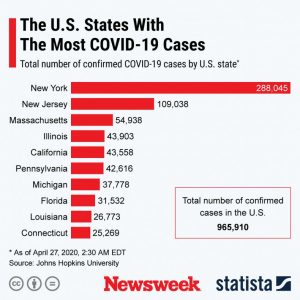

Across Massachusetts, the state Department of Developmental Services had recorded 782 confirmed cases of the coronavirus among individuals who receive DDS residential services as well as 929 cases among staff members — both state and provider employees — as of Sunday. Thirty people among the individuals served had died as a result of COVID-19 complications.

Like every facet of the health care system, the global pandemic has unleashed new challenges for residential programs serving individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. DDS programs reach 1,100 residents in state-run homes while 10,000 people live in provider-run homes.

In many instances, staffers like Gilliam are living at group homes for weeks on end to keep the virus at bay.

“It’s been a real challenge, and it’s been extraordinary,” said Bill Stock, vice president of government and community relations at the Seven Hills Foundation.

The foundation, which operates about 114 facilities statewide, has locked down approximately 70 residences due to the outbreak. Residents are “extremely vulnerable,” Stock said.

“You got to go to such extreme measures to protect these individuals to make sure they stay healthly and stay safe throughout this crisis,” he said.

Guidance from the state

At Seven Hills, those precautions are informed by guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and from DDS.

The state updated its recommendations — which state-operated facilities in Hathorne and Wrentham are required to follow — on April 13, stating that staffers should wear face masks for the entirety of their shifts; that providers can make emergency requests for personal protective equipment through the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency; and that mobile testing would be available for residents and staff in DDS programs, among other updates.

All staff are required to comply with a health screening when entering a building and will be turned away should they exhibit a fever or other coronavirus symptoms, according to the guidance.

Visitors are also barred from entering homes, “except for certain compassionate care situations, such as an end-of-life situation,” the guidelines say.

“We continue working with our provider agencies to ensure these important safety measures are implemented consistently across all of our programs and challenges are quickly addressed,” a DDS spokesperson said in a statement.

The department had recorded 47 resident and 62 staff virus cases in its Hathorne center, and 30 residents and 36 staffers had been diagnosed with the coronavirus at its Wrentham facility as of Sunday, according to officials. Two residents have died in Hathorne: two men, one in his 60s and one in his 70s, both with underlying health conditions, the department says.

All positive residents in the three-building Hathorne complex have been quarantined in a separate unit with specific staff assigned to only that unit.

Mobile testing of residents and staff in all DDS residential programs was launched earlier this month, and the department “is developing quarantine sites at three of our facilities to provide an alternative residence for individuals who are not able to safely quarantine in their group home,” the spokesperson said.

Life in lockdown

Last month, as the widespread impacts of the health crisis came into view, the New England Center for Children offered its staffers the option, should they desire to do so, to work away from the Southborough nonprofit’s private 15 group homes as they began self-isolating.

School programs shifted to remote learning to protect personnel and the over 125 students who live in the homes and attend classes.

And while students in the center’s day program would be refined to living at home, for autistic students who live in the group homes “there was no alternative,” Vinnie Strully, the center’s founder and CEO, said. The homes would need to stay open.

Over 100 of the caretakers declined to step down from their assignments, opting to keep working through the pandemic with the children, according to Strully.

Now, when not at the homes, they’re self-isolating in hotel rooms provided by the center, keeping away from others — and their families — when they’re not on the clock, Strully said. They also receive hazard pay for their work.

“It’s really amazing what they’ve dedicated to these jobs,” Heather Morrison, director of administration, told Boston.com.

Visitors — including parents of the students — are barred from stopping by. Deliveries are “carefully handled and processed,” Strully said.

Strully credits those early decisions for helping to maintain a low level of infections. So far, three people have tested positive for the coronavirus in two residences along with four staffers, two of whom have recovered and are now back at work, he said.

The first case cropped up six weeks into the lockdown and came from a staff member who was asymptomatic, he said.

According to Strully, the state has supplied the center with test kits its nurse practitioners can administer, technical support, PPE, and “everything we need to transition from a school to a half-school, half-medical setting.”

“We were well prepared for it,” he said. “We were waiting for the other shoe to drop for weeks.”

Meanwhile, the community at large, specifically many friends of the center, have offered what they can to help out by way of donations, particularly PPE, Strully said.

“Everyone has pitched in for us. … Our entire community has answered the call,” he said.

According to Stock, of the Seven Hills Foundation, MEMA recently supplied the organization with 5,000 face masks and 100 thermometers.

To complement the supply, “hundreds upon hundreds” of donations have poured in from the public, he said.

“It’s amazing how far people are going to help in this situation,” Stock said.

According to Stock, the number of cases the foundation has seen in its facilities is “extremely minimal” considering the number of people in its care.

“We’re not anywhere near out of the woods with this situation, but we’re encouraged right now,” he said.

Needless to say, life in lockdown is not without its challenges.

Many residents do not fully understand why their regular routines have been upended, why visits from parents and loved ones are now limited to FaceTime calls and Zoom sessions, their caretakers say.

“It’s a little bit hard for them to understand how long it’s going to take,” Gilliam, of Seven Hills, said.

Roberta Biscan’s 15-year-old son Connor, who lives in a Hopkinton group home run by the Center for Children, often tells his mother he misses going to school and that he needs a hug, Biscan told The Boston Globe earlier this month.

He is aware there is a virus but doesn’t understand why he can’t go home on the weekends like he used to, she said.

“It’s extremely hard not being there to comfort or reassure him,” Biscan told the newspaper.

Tracy Atkinson hadn’t seen her son Michael, 27, a resident at a Westwood group home, in two weeks when she spoke to the Globe a few weeks ago. She tries to comfort him when he calls.

“When your loved one doesn’t have the capacity to understand (what is happening) it’s particularly heart-wrenching,” Atkinson said. “Being able to see him smiling and him enjoying hearing us and seeing us has been a lot of comfort right now.”

Those calls from relatives have become a staple part of the day at Swan House, according to Gilliam.

Outside of that and mealtime, no two days are the same, she said.

“We’re just always doing something,” Gilliam said. “It’s more for the folks who live here (so they are) not being too concerned about what’s going on and why they can’t go outside.”

The staff tries to keep things fun. They throw dance parties, host movie nights complete with popcorn, and sit out on the deck when the weather allows, she said.

“We do just about anything to keep it not as boring” as it could be, Gilliam said.

As for the staffers, the biggest challenge is seeing their own families only over video calls, she said. Gilliam was slated to work until a new round of workers picked up the shifts on Tuesday.

But being at the home has provided a peace of mind of its own. Staying in isolation means residents are safe, and so are the staffers and their families, too, she said.

And Gilliam loves her job.

“This is my other family,” she said. “So if I was going to be anywhere other than home with my family, I would want to be here.”