When the coronavirus arrived in the United States, it took many doctors and medical professionals by surprise. Alberto Paniz-Mondolfi was not one of them. He also wasn’t shocked when, a few months later, small numbers of infected children began exhibiting strange, widespread inflammatory symptoms. As someone who spent years fighting epidemics in South America, he learned how pathogens spread and what they can do.

“When you deal with these guys, you kind of develop an instinct,” he said. “It’s like you can smell them.”

Paniz-Mondolfi, M.D., Ph.D., is an assistant professor of pathology, molecular and cell-based medicine at the Mount Sinai Icahn School of Medicine who has studied and treated some of the most horrendous infectious diseases in the Western Hemisphere. When he was forced to flee his home country of Venezuela during economic and political turmoil in 2019, he thought his battles against mysterious contagions would ease up — at least for a while. But then he was thrust into the center of one of the world’s most deadly pandemics.

Now he is trying to solve a pressing and vexing Covid-19 mystery using clues from his past infectious encounters: Why does the coronavirus, which largely spares children, make a very small proportion of them very, very sick? And why so often children who are Black? Or Latino, like him?

Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi, 43, a father of two, was born in Venezuela, but split his childhood between there and Kenya, where his grandfather, a biologist, was an ambassador. His love for viruses was inspired in part by a safari to Kitum Cave in Mount Elgon National Park in Kenya in the 1980s. During the visit, his grandfather told him that, several years earlier, bats had infected tourists there with Marburg virus, a relative of Ebola. He had arrived hoping to see elephants but left fascinated by the microbial universe.

Even with a mother as a pediatrician and two uncles as well-known Venezuelan physicians, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi wanted to do more than clinical medicine as a career. As he got older, he also wanted to study infectious diseases. During his doctoral studies in Venezuela, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi worked with a Venezuelan physician scientist, Jacinto Convit, M.D., a pioneer in leprosy research.

After Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi earned a master’s degree in parasitology and tropical diseases in 2006, he completed fellowships around the world in microbiology, molecular genetics and skin disease, and a second residency in the United States in pathology. During that time, he isolated and described a new species of parasite that had infected a man in the Bronx, as well as a new mycobacterium that sickened two Connecticut residents.

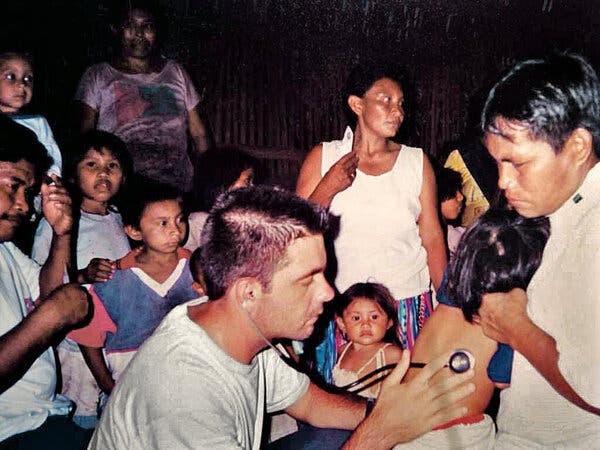

Then Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi returned to Venezuela, where he studied and treated patients with diseases like dengue, Chagas’ disease, chikungunya and Guanarito virus, a mysterious hemorrhagic fever that kills nearly one in three people it infects. In 2018, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi and his team were among the first in Venezuela to identify the Madariaga virus, a mosquito-borne pathogen that can cause fatal brain infections.

Gustavo Benaim, Ph.D., a biologist at the Universidad Central de Venezuela and the former adviser of Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi during his doctoral studies, described him as “a fearless virus hunter.” He added, “He is an extraordinary clinician and microbiologist.”

Latest Updates: The Coronavirus Outbreak

Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi said he then became fascinated by the lingering effects of some viruses, especially in children. The Western plains of Venezuela, where he lived, is a hot spot for dengue and Kawasaki disease, an inflammatory syndrome in children that can cause heart complications. Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi has long suspected a link between the two. Dengue is mosquito-borne and he knew Kawasaki diagnoses peaked in Venezuela when mosquitoes were most rampant. He also knew that Kawasaki disease sometimes is preceded by serious infections. Based on those characteristics, he and his colleagues argued in a paper published last month that dengue most likely leads to Kawasaki disease in some Venezuelan kids.

Despite his grisly profession, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi is congenial and upbeat. He referred to the viruses he works with as if they were buddies; dengue is “an old friend,” whom he used to see “on a daily basis.” Mayaro virus, which causes high fevers and joint pain, however, was “a pretty nasty guy.” Yet despite the casual nicknames, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi obsesses over each micro-organism and its quirks. He doesn’t just want to tame them to save his patients — he wants to deeply understand them to predict their next move.

Zika hit Venezuela in 2015 and brought Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi some of the most puzzling cases he had ever seen. One patient developed Alice in Wonderland syndrome, in which she perceived her body parts changing sizes, sometimes looking huge, in her mind, sometimes tiny. The epidemic hit amid an economic and political crisis in Venezuela, and Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi was soon caring for nearly 400 patients at once on a shoestring budget as he scrambled to better understand the infection.

“It was emotionally devastating to see these babies bursting with seizures and not being able to provide them treatment. No parent deserves to live a situation like this,” he said. At the time, he had a newborn son, but he and his wife, who is a biologist, couldn’t even get diapers and he milked his father-in-law’s cows and goats to feed his child.

“There was no power in the whole country. No water. It was terrible,” he recalled.

To run his lab, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi, who could barely provide for his family, had to sneak supplies into the country. Once, as he walked his kids to school, he noticed his 7-year-old wearing broken shoes; he knew he couldn’t afford a new pair. “I got in the car and cried nonstop for about an hour,” he said.

Still, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi and his student lab members managed to publish more than a dozen papers during the outbreak, including the first to describe Zika transmission through breastfeeding.

Peter Hotez, M.D., Ph.D., the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, said, “Alberto has been one of my key windows into what’s actually going on in Venezuela. He’s been committed to showing how diseases become an instrument of human rights violations in Venezuela, and that’s been critically important.”

The Venezuelan government, however, was not pleased, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi said. He suspects that, because his research highlighted problems in the country with re-emerging and endemic infections, it was interpreted as a conspiracy.

In 2019, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi realized he needed to flee Venezuela — and quickly. He said he began receiving anonymous threats over the phone and social media, and his colleagues and friends, including a former professor, warned him to leave the country. “They were either going to kill me, or they were going to put me in jail,” he said.

Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi moved to New York and joined the faculty at Mount Sinai. He assumed he would get a respite from his work battling deadly epidemics.

He didn’t. When the first known New York City Covid-19 patient came to Mount Sinai, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi was on duty in another wing.

As more cases came in, he began to worry — but not for the reasons everyone else did. He worried the medical community was underestimating the coronavirus’s potential effects on children. Most U.S. doctors have “never lived through a dengue epidemic,” he said. His experiences in Venezuela with that virus, and its inflammatory aftereffects in children, gave him nightmares about what to expect next.

Although coronavirus and dengue are different in many ways, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi noticed several similarities. Both viruses target endothelial cells, which line blood vessels. With dengue, blood can slowly seep out of patients’ veins, causing shock and death; the coronavirus too, injures blood vessels throughout the body. With dengue, case reports have suggested that this blood vessel damage may trigger an exaggerated inflammatory response that can possibly lead to Kawasaki disease. Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi wondered if the same would happen with some children who have Covid-19 — that they may experience a similar dangerous post-infectious inflammatory syndrome. When viruses “hit the endothelium, there’s no good news,” he said. “I could not get Kawasaki out of my mind.”

Most children who catch the coronavirus only experience mild symptoms. But a few months after the coronavirus struck New York, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi’s hospital began treating a small number of seriously ill children, most of whom had been infected with Covid-19 weeks earlier. The condition came to be known as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C. Kids with MIS-C usually have severe abdominal pain, high fevers, vomiting, diarrhea and sometimes sprawling rashes or bloodshot eyes. Often, they have to be hospitalized and can experience damage to multiple organs — characteristics immediately recognized as similar to Kawasaki disease.

As of September 3, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had received reports of 792 MIS-C cases in the United States and 16 deaths; 20 have been treated at Mount Sinai as of Aug. 27. Of those nearly 800 cases, more than 70 percent have been either Black or Latino. A C.D.C. study published in August found that the rate of hospitalization for Black children with Covid-19 is five times higher than it is for white children, and the rate for Latino children is eight times higher.

Faced with a deluge of MIS-C cases at Mount Sinai in May and June 2020, Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi and his colleague Mariawy Riollano-Cruz, M.D., a pediatric infectious disease physician at Mount Sinai, immediately noticed the racial discrepancies, as they reported in a study published in June. They wondered why. Perhaps the trend could be explained by the fact that communities of color have higher rates of Covid-19 than white communities do and more Covid-19 cases leads to more MIS-C cases.

But the math doesn’t fully add up, at least for Black children. In a systematic review published in August, C.D.C. researchers pointed out that about 20 percent of all of New York’s Covid-19 patients are Black, based on a survey of adults, but 40 percent of MIS-C patients are. Likewise, a national study looking at 186 patients found that 25 percent of MIS-C patients in the United States are Black, yet C.D.C. data suggest that only 19 percent of U.S. Covid-19 patients of all ages are (though race and ethnicity data are only available for about half of all cases reported to the C.D.C.). Among Latino children, the percentages match up more closely, but are still higher than expected.

Because access to testing is limited in minority communities, it may be that Black and Latino Americans are catching the coronavirus at higher rates than these test percentages suggest. If so, Black and Latino children may be developing MIS-C at rates that would be expected based on their exposure to Covid-19.

Drs. Paniz-Mondolfi and Riollano-Cruz wondered, though: Could there be something that puts these children more at risk for developing MIS-C when they get the coronavirus? They suspect the problem is multifaceted, and others agree. “There are numerous factors that disproportionately impact disadvantaged minority groups, such as insufficient access to health care, higher prevalence of underlying medical conditions and increased exposure to environmental pollutants,” said Joseph Abrams, M.D., Ph.D., an epidemiologist and a member of the C.D.C.’s MIS-C investigations unit. These inequities “are known to be linked to increased severity for other health conditions, and it is plausible that these factors also play a role in risk for MIS-C.”

It’s possible, too, Drs. Paniz-Mondolfi and Riollano-Cruz said, that susceptibility has a genetic component. Perhaps there is a genetic variation in an immune-related gene that puts certain children at risk, regardless of race, since race is not determined by genes. It makes sense to them that genes could play a role, because genetic variations have been linked to Kawasaki disease. Drs. Paniz-Mondolfi and Riollano-Cruz are designing genetic studies to find out if the same is true for MIS-C.

Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi said he hopes that, by identifying risk factors, doctors will be able to prevent MIS-C — or at least make it more treatable. Physicians could then closely monitor children deemed to be high risk and get them necessary care earlier. Dr. Paniz-Mondolfi also can’t help but think of children in Venezuela, where the coronavirus is beginning to hit hard, and where MIS-C may not be far behind.

“It’s a race against time,” he said.

Melinda Wenner Moyer is a science and health writer and the author of a forthcoming book on raising children.