If quarterback Drew Lock throws a touchdown pass and Broncos Country doesn’t roar, it’s still worth six points on the scoreboard. But somehow the score feels hollow because it doesn’t resonate where football counts the most, deep in the gut of 75,000 screaming fans that bring an NFL game to life.

At 81 minutes before kickoff of Denver’s game against Tennesee, I strolled the stadium’s lonely concourse, past hot dogs with nobody to love them and empty bathrooms, looking for the father of Broncos guard Dalton Risner, when my phone rang.

“I shouldn’t be hard to find me,” Mitch Risner said early Monday evening. “I’m the only guy in Section 106.”

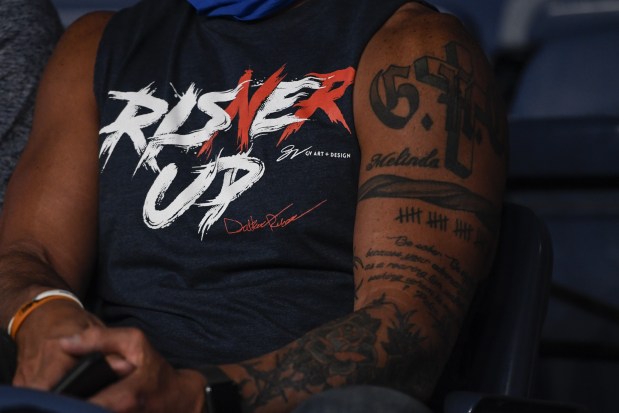

Sure enough, I found a football fan as strong as a bull, standing all alone 20 rows above the 40-yard line. He wore a sleeveless Risner-Up shirt that revealed two things:

No. 1: Beautiful tattoos of an old, rugged cross and rope adorning the muscles of his left arm.

No. 2: Mr. Risner apparently never got the memo that in middle age it’s OK to have a Dad body.

During 61 seasons of pro football in Colorado, there’s never been a home-opener like this one. And after the coronavirus pandemic fades, let’s hope there’s never one like it again.

It felt as if Lock was playing at the library rather than in Broncos Country.

“I can’t wait until we all get back to normal. But no fans will block my view and nobody will have to ask me to sit down after a touchdown,” said Risner, whom I’m betting could win two out of three falls in a rasslin’ match with his 312-pound son, who wears No. 66 in the Broncos huddle. “This is kind of weird. Nobody’s here. But I’m from Wiggins (pop. 996), so I’m used to it.”

On this beautiful late-summer night, Risner was among the 500 friends and family of players and Broncos staffers allowed to cheer the sport Colorado loves best. A loving father, who has coached the team’s second-year offensive guard since childhood, followed his usual game-day routine.

“Dalton wants to know on Play No. 7 of the game, whether he had a misstep off the line or leaned forward too much against a pass-rusher,” said Risner, who takes copious notes on every minute detail of his son’s blocking technique during home games. “It’s not that I coach him. He has NFL coaches to do that. But after the game, he wants to connect with his Dad on that deep football level.”

But can you keep a secret?

It wasn’t the same without the 75,000 spectators that make Broncos Country so beautiful.

“Very disappointing,” said Miles Power, the Aurora resident who had his personal attendance streak of 268 games, never missing a single play home or road since 2004, broken by the abundance of safety precaution that prevented loyal season ticket-holders from being in the stands.

Echoing the heartbreak of Broncomaniacs, Power said last week, upon realizing his 16-year-old streak was doomed to end: “What has stung me more than anything is the lack of care and outreach by the Broncos. While I always knew my love was unrequited, the lack of care and consideration throughout this process has made it more glaring than I could’ve ever imagined.”

It’s a sad football season in Denver, no matter your opinion of the coronavirus regulations enacted to curtail the number of deaths from this wicked disease. The restrictions also threaten the life of restaurants, movie theaters and any number of businesses that make hard-earned income by entertaining us between Broncos games.

Nothing stops the NFL money machine. While it was good to see Denver native Phillip Lindsay toting the rock for Denver, what I really miss is the Friday night lights that have been turned off on prep football players.

Nobody understands what the game means to an adolescent boy than Mitch Risner. He’s a high-school football coach in a rural Colorado town, where farmers lean on the fence behind the home team’s bench and second-guess him in real time after every failed third-down play forces the Tigers to punt.

AAron Ontiveroz, The Denver Post

Mitch Risner watches his son, Denver Broncos lineman Dalton Risner, during the first quarter against the Tennessee Titans on Monday, Sept. 14, 2020.

“I will admit, it’s a really difficult time right now. And not just because kids cannot have games of football that they love,” Risner said. “It’s everything else the sport does for adolescent boys in giving them motivation to keep their grades up and having the time to bond at every practice and keeping them busy after school while their parents are at work.”

Depending on the day, Gov. Jared Polis and officials from the Colorado High School Athletic Association either sound ready to resume a season put on hold by coronavirus concerns, or decide to punt again until spring.

“We’re getting so many mixed messages: There is going to be a season. There isn’t going to be a season. It’s getting to the point where everybody is confused and nobody knows what to believe,” Risner said. “All this uncertainty is hurting these young players. It’s such a roller-coaster ride for these kids.”

The NFL is football’s biggest stage.

But touchdowns count more in Wiggins, where every score is a childhood dream come true.